The Bible and big ideas

The Bible: Wisdom Literature

A New Series By Candace R. Kwiatek, The Dayton Jewish Observer

During my search for Passover vinegar to make fresh horseradish, I was asked, “Why is Passover vinegar different from everyday kosher vinegar? And what about Passover wine — isn’t wine fermented like yeast bread? And how can Passover recipes call for leavening ingredients like baking powder or baking soda?”

Although reasonably well-educated, I couldn’t explain. So off I went to learn.

Even though text and electronic resources are great, actually finding the answers when you want them can be difficult.

When you do, they’re frequently lengthy and detailed, technically correct but devoid of context, or glaringly contrived or outdated.

Thus, the response of many contemporary Jews is, “When we can’t reasonably explain our traditions, when commands seem to have no purpose other than blind obedience, when laws and texts are contradictory, or when explanations are archaic or simply fabricated, it’s hard to take such things seriously.”

This amalgam of real comments from serious Jewish millennials got me thinking.

On the one hand, their questions and challenges are encouraging because they suggest a willingness to engage and consider. On the other, I’m pretty sure we’re missing the point when we respond.

According to Gallup research, millennials “don’t accept ‘that’s the way it has always been done’ as a viable answer.”

At the same time, “they believe that life…should be worthwhile and have meaning. They want to learn and grow.”

Certainly, Judaism infuses life with worth and meaning and offers endless opportunities to learn and grow.

When fielding specific questions about Jewish life, lore, and tradition, we rarely address these underlying big ideas. Three Torah worldviews illustrate Judaism’s possible responses to these big ideas.

Divine document

Traditionalists across the spectrum view the Torah as a Divine or divinely-inspired document. The text is inerrant, or at least close to it insofar as human beings physically recorded it, and it’s the highest authority on all matters of behavior, meaning ethics are absolute.

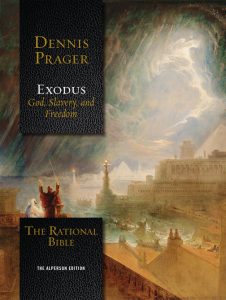

As Jewish commentator Dennis Prager puts it in The Rational Bible: Exodus, “When I differ with the Torah, I think the Torah is right and I am wrong.”

As for conflicting or uncomfortable texts, scholars may offer interpretations, but ultimately traditionalists are not afraid to concede, “I don’t understand.”

The traditional approach is attractive to many millennials for its clarity and personal focus.

It teaches that each human, created in God’s image, has infinite value and that life’s ultimate purpose is to bring holiness to the world through one’s actions.

Thus, learning that encourages ongoing moral and spiritual growth is emphasized, and the Bible as a timeless primary source of guidance and wisdom is to be studied regularly.

Documentary hypothesis

Liberal traditions view the Torah as a historical document, a set of creation myths, legends, history, stories, customs, institutions, and beliefs that arose organically or were deliberately created to explain the origin of the Jewish people and its relationship with God.

Because of differences in style, language, and contradictions in the texts, scholars conclude multiple authors must have written the Torah, perhaps by modifying and incorporating pre-existing texts. A living document, the Torah continues to develop over time in response to changing historical and societal conditions.

With its communal focus, the more analytical historical-literary approach connects with millennials’ ideas about living a worthwhile and meaningful life.

The individual, made in God’s image, is also God’s partner in repairing the world. Intellectual development and moral improvement are communal tasks as well as individual ones, as part of the world’s repair.

Rational Bible

Far too many Jews, however, are not inspired by Divine or documentary Torah views. Turning to the internet, friends, travel, even their feelings as their personal gurus, today’s Jews are missing out on the greatest resource of all for a meaningful life and personal growth: Torah.

Highly-educated, well-read, and world-savvy, they need relevant texts and responses in modern language that not only make sense but also make a difference. A rational approach offers another option.

Highly-educated, well-read, and world-savvy, they need relevant texts and responses in modern language that not only make sense but also make a difference. A rational approach offers another option.

“My approach to understanding and explaining the Torah is reason-based…reason has always been my primary vehicle to God and to religion,” writes Rational Bible author Dennis Prager.

Reason is a pathway to wisdom, which is linked to goodness, Prager notes, “because it is almost impossible to do good without wisdom.”

Thus, a kinder, more just world can evolve from a rational approach to the Bible, addressing millennials’ deepest desires.

Millennials aren’t the only ones seeking meaningful and purposeful lives, learning, and growth; they’re just the ones in the surveys.

We’re all seeking to some extent. The problem is, we rarely have the opportunity to discuss or respond to these big ideas. They’re hidden quietly underneath more mundane queries about Passover wine or God’s hardening of Pharaoh’s heart or what it means to love the stranger.

So maybe next time we have or hear a specific Jewish question, no matter our background or biblical worldview, we should take a moment to think how our response could be even more meaningful by integrating a thought or two about one of these big ideas.

Literature to share

The Rational Bible: Exodus — God, Slavery, and Freedom by Dennis Prager. This just-published volume is the first of Prager’s written biblical commentaries, the outgrowth of a half-century of studying and teaching Bible, ethics, history, and virtually every other topic to students of widely varied backgrounds, ethnicities, and worldviews, both religious and secular. Instead of offering commentary in footnotes or addenda, Prager has included analyses, stories, examples, quotes, and more as part of the book’s text, making the experience of reading more like a conversation than a solitary endeavor. His purposes are to demonstrate the rationality and contemporary relevance of this unparalleled text, reveal how its ideas can better our lives, and show how faith and reason can live in harmony. Highly recommended.

The Art Lesson: A Shavuot Story by Allison Marks. What a delightful addition to the sparse children’s literature for Shavuot, and for any season. Shoshana and her grandmother have a weekly date for a creative art adventure involving paint, or maybe glitter or clay. This week’s project introduces a traditional activity for Shavuot: papercutting. The whimsical and wildly colorful illustrations hint at various artists’ styles — Chagall, Matisse, African masks — and the vocabulary is a child’s treasure chest: skeleton key, vial, beret. I love this book!

To read the complete May 2018 Dayton Jewish Observer, click here.