How 1917 Battle of Jerusalem surrender flag ended up in Greenville, Ohio

By Marshall Weiss, The Dayton Jewish Observer

Few at Israel’s commemoration in December marking the centennial of the Ottoman surrender of Jerusalem to the British during World War I would know that the main portion of the surrender flag is housed at a museum in Greenville, Ohio.

And visitors to the Garst Museum and Darke County Historical Society in this small city 40 miles northwest of Dayton are more likely aware of its exhibits about Darke County’s Annie Oakley, and the 1795 Treaty of Greenville with Native American tribes, which opened much of Ohio to United States’ settlement.

But for more than 50 years, the 1917 Jerusalem surrender flag has been on exhibit as part of the permanent collection at the Garst.

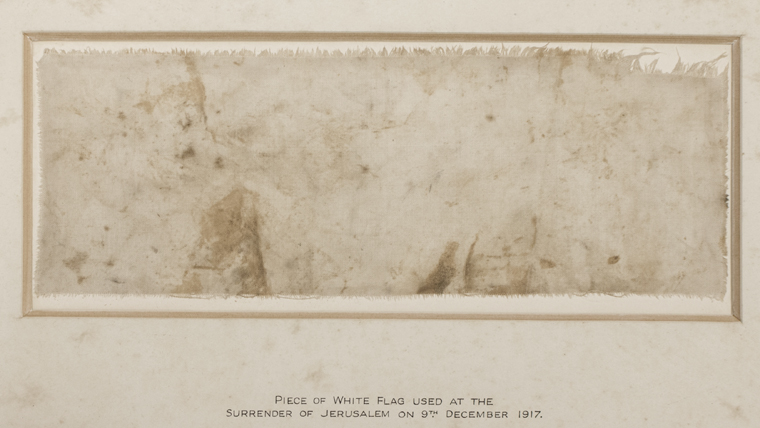

A smaller portion of the surrender flag is on exhibit at the Churchill War Rooms of the Imperial War Museums in London.

“This flag represents probably the most significant and historic artifact in this museum for what it represents to world history,” said Dr. Clay Johnson, president and CEO of the Garst Museum since 2010, and the museum’s only full-time employee.

The surrender flag is part of the third major exhibit area at the Garst, which focuses on the life of Darke County native Lowell Thomas (1892-1981), the longtime news reporter and world traveler.

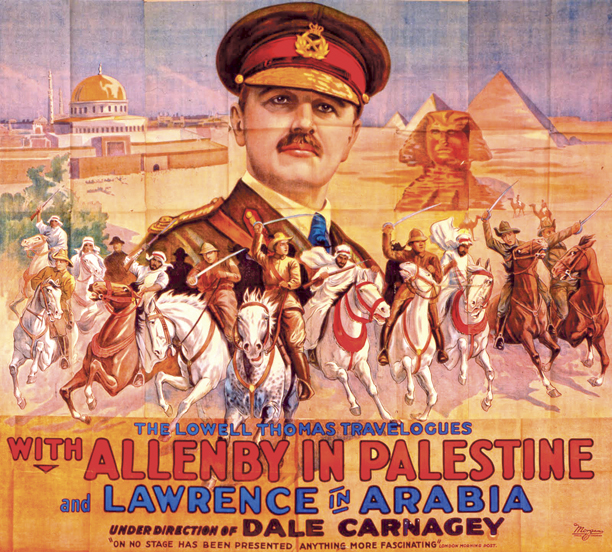

Before his radio career with CBS and NBC, which spanned from 1930 until his retirement in 1976, Thomas created the travelogue genre of film.

At the urging of President Woodrow Wilson’s Cabinet, Thomas and his cameraman, Harry Chase, embedded with British Gen. Edmund Allenby’s army on its way to Palestine in 1917, to capture footage of the campaign.

Following the war, Thomas met with much success when he toured England in 1919 with his two most popular documentaries, With Allenby in Palestine and Lawrence in Arabia; he had befriended the British military officer after the Battle of Jerusalem.

It was in London in 1919 where Thomas said he received half of the Jerusalem flag of surrender from a Canadian colonel who was responsible for compiling artifacts for Britain’s Imperial War Museum.

“He came to me one day almost with tears in his eyes,” Thomas recalled of the colonel in a 1972 interview with the Los Angeles Times. “He said, ‘They’re piling the stuff out at Crystal Palace, on the outskirts of London, just piling it in heaps, and it’s a mess. I think that you, because of your special interest in the Palestine campaign and what you’re doing, are entitled to have some of these things, so I’ve brought you some.’”

Thomas added, “he gave me the white flag of surrender — half of it. The other half he said he was keeping.”

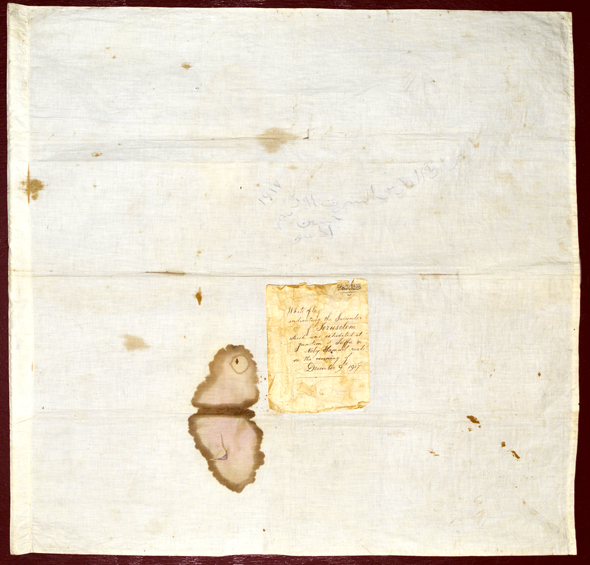

The flag portion, which measures 35 by 37 inches, was part of a cache of artifacts that Thomas donated to the Garst Museum in 1966 for its then new Lowell Thomas wing.

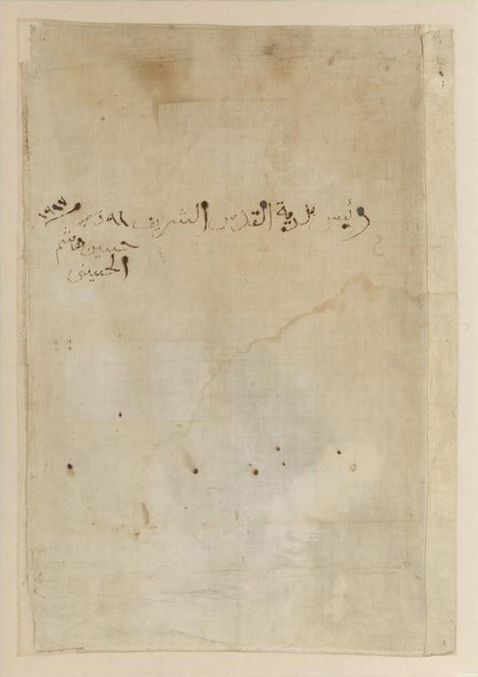

A page of stationery from the “Department of the Municipality of Honored Jerusalem” attached to the portion of the flag in Greenville states: “White flag indicating the Surrender of Jerusalem which was exhibited at junction of Jaffa & Neby Samuel roads on the morning of December 9th 1917.”

The Garst Museum loaned its portion of the surrender flag to the Imperial War Museums in London for its Lawrence of Arabia exhibition in 2005-06.

“The Imperial War Museums renovated and restored the flag as part of the agreement,” Johnson said.

In preparation for the centennial of the surrender, curators for a new exhibit at the Tower of David Museum in Jerusalem, A General and A Gentleman – Allenby at the Gates of Jerusalem, asked to borrow the flag from the Garst earlier this year.

The Tower of David Museum is steps away from where Allenby walked into Jerusalem as a “pilgrim” at the Jaffa Gate on Dec. 11, 1917; the victorious general then addressed Jerusalem’s citizens from the steps of the entrance to the Tower of David Citadel, with the promise that he would protect all of the holy sites “of the three religions.”

Exactly 100 years later, The Tower of David Museum reenacted the events and officially opened its new Allenby exhibit, without the Garst’s artifact.

“It’s sealed away in our case,” Johnson said. “We wouldn’t be able to loan it.”

Instead, Johnson provided the curators in Israel with high-definition images of the flag for their exhibit.

He also sent them a digital file of a documentary film Thomas produced in 1968 featuring a firsthand account from Thomas’ friend, Bertha Spafford Vester, the hospital nurse in Jerusalem who provided the city’s mayor with the surrender flag.

Overnight on Dec. 8 and 9,1917, the Ottoman Turks evacuated Jerusalem and handed its mayor, Hussein al-Husayni, a letter of surrender to give the British, ending 400 years of Ottoman rule over Jerusalem.

Before venturing out to surrender to the British on the morning of Dec. 9 — also the first day of Chanukah — the mayor visited the American Colony. He asked Vester’s mother about the proper protocol for surrender. She told him to bring a white flag. Vester took a sheet from a hospital bed, tore it in two, and gave the mayor half to use as the white flag, held aloft on a broomstick.

That would be the easiest part of the mayor’s day. According to several accounts, al-Husayni attempted to surrender six times on Dec. 9: the first four attempts involved low-ranking British soldiers who felt unworthy of the honor or were just confused, the fifth and sixth were with Brig. Gen. C.F. Watson at 9:30 a.m. and then with Maj. Gen. John Shea on behalf of Allenby at 11 a.m.

It was Watson who in 1919 donated half of the surrender flag to the Imperial War Museums in London.

Both halves carry the signature in Arabic of Mayor al-Husayni, who died only a few weeks after the surrender.

Curators with the Tower of David Museum also asked to borrow the Imperial War Museums’ portion of the flag — which measures 34 by 23 1/2 inches — “but as we required it for our own displays, the request was rejected,” a spokesperson for the Imperial War Museums said.

As of last summer, staffers at the Tower of David Museum were concerned they would have no surrender flag for the exhibit, Caroline Shapiro, a spokesperson for the Jerusalem museum, said.

“How can you have an exhibit about the surrender without the surrender flag?” Shapiro said. “Then, as staff went through pieces of our collection, one opened a framed picture and an envelope fell out of the back with a piece of the flag inside, and documentation from the IWM,” Shapiro said. “We couldn’t believe it.”

Along the way, someone had cut and saved a piece of the flag of about 12 by 8 inches. According to the Tower of David Museum’s records, the remnant was a gift from the estate of the widow of Lt. Col. A.E. Norton, “who collected the flag from the field after the surrender.”

This third flag portion is part of the Allenby exhibit at the Tower of David, which runs through September.

Johnson said few visitors come to his Greenville museum specifically to see the flag.

“I have had people come for Lowell Thomas, some researchers, a couple of World War I historians. What this represents is kind of lost here in the United States. The flag, in my opinion, really represents this transformation into the modern-day Middle East. They’re (the British) the ones that redrew the modern Middle East borders, haphazardly in today’s context. It could be argued that they didn’t take any of the cultural significance of where the borders were drawn.”

Faced with a generational challenge to keep the legacy of Lowell Thomas relevant, and on a shoestring non-profit budget, Johnson said he aims to “tell the story of history through Lowell Thomas instead of trying just to tell the story of Lowell Thomas.”

To read the complete January 2018 Dayton Jewish Observer, click here.