What we did and didn’t learn

Part Three

Conclusion: Black/Jewish relations from the Dayton riots through desegregation

By Marshall Weiss, The Dayton Jewish Observer

Thursday, Sept. 2, 1976 marked day one of Dayton Public Schools’ implementation of its court-ordered desegregation plan to achieve racial balance.

According to an Associated Press story, the first day of busing students across the city went “as smooth as silk,” with no demonstrations of any kind.

It was also nearly a year since serial killer Neal Bradley Long had shot and killed Dr. Charles Glatt — the Ohio State professor assigned by the federal court to carry out the desegregation order in Dayton.

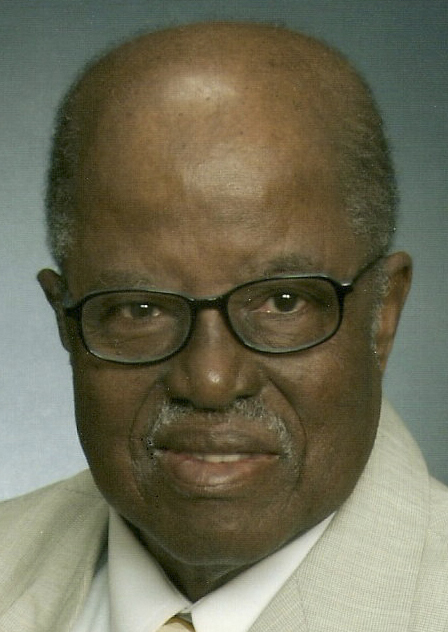

“We won the desegregation, but we didn’t win anything,” said Jessie Gooding, who served as a vice president of the Dayton NAACP at the time.

Dayton’s chapter was a driving force behind the 1972 federal lawsuit to integrate Dayton Public Schools, a case that would make its way to the U.S. Supreme Court and back to Federal district court. Gooding would lead Dayton’s NAACP as its president from 1985 until his retirement in 2003 — a year after NAACP and Dayton Public Schools reached a settlement to end the failed desegregation program.

“The schools are more segregated now than they were in the ‘70s,” Gooding said.

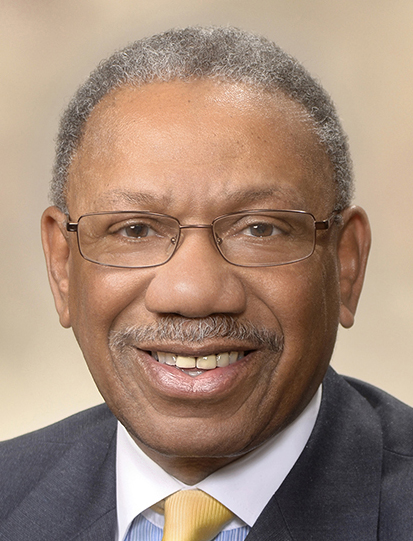

“It was the law of unintended consequences,” said U.S. District Judge Walter H. Rice, who inherited oversight of the implementation of the desegregation order for Dayton Public Schools when he was appointed a Federal judge for southern Ohio in 1980.

“The motives were good, but it precipitated not only the flight of the white middle class, but also the flight of the black middle class,” Rice said. “And that’s when Dayton’s descent into poverty, I believe, began, because areas were left with no white or black middle-class role models or mentors.”

From 1960 to 2016, Dayton’s population plummeted from 262,332 to 141,527. Student enrollment in Dayton Public Schools went from 60,633 in 1965 to 14,000 today.

“It went like a rock,” said Dan Baker. He and his wife, Gwen Nalls, are the authors of Blood in the Streets: Racism, Riots and Murders in the Heartland of America, which chronicles Dayton’s racial struggles from 1966 through 1975.

“No matter what else was being fixed inside the city, it was clear that the city was going to decline because of the population,” Baker said. “Probably one of the most significant things that drove so much movement out of the city was the fact that they elected to do a district-wide plan, not a regional plan like Indianapolis or other places where Dr. Glatt had been. No one would have had the stomach for a regional plan anyhow. They can’t even, for a regional operating government, as we already know right now.”

Joe Bettman was among the desegregation activists who attempted to persuade suburban districts to join Dayton’s desegregation efforts, fully knowing how unlikely those districts would be to sign on.

“How can you desegregate if you don’t have anybody to desegregate with?” Bettman said.

“A national education maven had set up desegregation in Tampa and one other city, and he came to speak to us in Dayton,” Bettman said. “His theory was if you integrate the schools and do the busing of the kids from the white neighborhoods and so on — because you have to remember back in those days there was very segregated housing — if you did that, the kids from very disadvantaged homes would show improvement in their scholastic achievements, and the kids from more advantaged homes would not suffer their education. That was the theory.

“Unfortunately, about five years after all this happened, I pick up a Parade magazine from the Sunday paper and this guy disavows: he misinterpreted his statistics. It was really devastating. We had worked so hard.”

Rice pointed out that at the time of desegregation, housing opened up, “where it was no longer permissible to deny a person housing because of race, color, religion.”

When asked what could have been done that might have brought more success to the attempt at desegregation, Rice said, “Other than barricading people into specific neighborhoods, I don’t know what could have been done.

“In the last 10 to 12 years, there has been a conscious effort on the part of government to disperse housing, to place lower income or lower middle class income whites and blacks into suburban communities. Had that occurred sooner, it might have eased some of the problem. But the political will was not there to do that in the 1970s.”

Dayton City Commissioner Jeff Mims taught at Belmont High School when desegregation was implemented. He would go on to serve as president of the Dayton Education Association, president of the Dayton Board of Education, and as a representative on the Ohio School Board.

“The sadness of it is — because society hadn’t done what it needed to do then — they forced the schools to do their job in terms of desegregating society,” Mims said. “The other sad part is, they did not give us what we needed. The only thing they gave the schools was a little bit of money for transportation. They did not give schools money for a strong level of professional development and training in helping the teachers and administrators understand why we’re doing what we’re doing, what we’re doing, and the purpose in terms of the whole process. We were left to figure it out on our own.”

Even so, Mims said the attempt at desegregation produced more pluses than minuses.

“It gave people a better sense of the fact that we had good people — white and black — and we had bad people — white and black,” Mims said. “And that neither race has a corner on the market. It gave people a better view of human dynamics. If the teacher was comfortable enough and used those teachable moments, it became a success.”

Robert Weinman, an assistant superintendent of Dayton Public Schools at the time of desegregation, said the integration of black and white teachers brought them together as friends, “not just on school issues, but personally, as they got to know each other better.”

“There were an awful lot of disciplinary problems,” Rice recalled. “People weren’t used to getting along. But the one thing I think we got out of deseg that I don’t think should be overlooked is, we learned to co-exist with each other on an equal basis. I mean, blacks and whites had always interacted but it was almost like an employer/employee basis. But here, our kids were forced to go to school together and they liked or disliked people because they were mean, they were bullies, not because they were black or they were white.”

“Thinking back, it was very uplifting because we saw good things happening too, and made good friends through the years, black and white, and non-Jewish and Jewish,” Elaine Bettman said.

“You’re talking to people who came through it and survived it happily,” Joan Knoll said of herself and her husband, Dr. Charlie Knoll. “And our children survived it happily. It made the (Dayton View) neighborhood more interesting. And now we live in a neighborhood (Northwest Dayton) where, believe it or not, not much needed to be done. We were already integrated by choice. It just happened.”

With African-American students comprising 73 percent of Dayton Public Schools’ population, in 2002 Rice presided over the settlement between Dayton’s NAACP and DPS to formally end desegregation in the schools and return to a neighborhood school program.

“There simply weren’t enough white children,” Rice said. At first, NAACP resisted the DPS request that Rice lift the busing order.

“It had been a monumental accomplishment for them,” Rice said of the Dayton NAACP, “and there was tremendous frustration that it hadn’t succeeded to the extent they had wanted it to, and they thought to remove the coercion of the busing order would make things worse.

“Their position was not totally unjustified, because by the time the busing order was dissolved and we returned to so-called neighborhood schools, a lot of those neighborhood schools no longer existed. They had been torn down, condemned as unfit, and the like.”

“It fragmented communities,” Mims said of Dayton’s attempt to desegregate. “There could have been so much more that we should have done, if there had been more money. It could have been so much better.”

Gooding said he still thinks the only way Americans will become equal as a society is to desegregate, but he doesn’t know when that will happen.

“The United States is funny,” Gooding said. “They ain’t ready. They ain’t got over slavery with black folks. Somehow or another, they want to keep us subservient for some reason. They’re not ready for us.

“By more than a stretch of the imagination Obama got to be president. And a lot of the repercussions come as a result of him being president. The hardness came when a lot of folks thought blacks went too far making him president of the United States.”

Baker, who began his career with the Dayton Police just before the 1966 riot, says the hopelessness he saw in the black community back then is as profound today.

“Hate, to me, is as prevalent today as it was before: hating somebody because they’re the police, or other groups hating one another. Killing cops and saying we’d like to kill you is not so much new,” Baker said. “The Black Panthers in Dayton wanted to shoot and kill police officers. The same shootings happened then.”

“We have got to understand what the issues are, not react to the social media, not react to the mainstream media, not react to those who are saying the cops are the problem,” said Blood in the Streets co-author Gwen Nalls, Baker’s wife. “The problem started when the industry left, the jobs left. Busing forced that out because the school systems declined and the corporations left.”

For decades, Rice has facilitated initiatives in the Dayton area to bridge racial divides. To him, the greatest obstacle is that people don’t feel they can truly improve the human condition. And they don’t have the drive to understand each other’s perspectives.

“At the same time, there’s been a decline in the effort of faith-based leaders to have a community ministry, to reach out to other parts of the community,” Rice added. “These things were the focus of the civil rights movement. I don’t think they exist today.”

“The reason I think there’s a divide,” Rice said, “not just between the Jewish community and the black community, but between the black and white community today is this: many people in the white community feel that they worked hard in the civil rights movement. We won. Everyone is on the same plane legally. Now it’s up to them (African-Americans) to move the ball down the field. They have no patience to listen to or to try to understand that racism today is even more entrenched, certainly harder to identify because it’s underground.

“Too many Jewish people say to African-Americans — because I’ve been present — ‘we know what it is to be black in the United States because we’ve been discriminated against and went through the Holocaust.’ Well, the Holocaust is the worst thing to ever happen to a racially-identifiable group that I can think of. But the average African-American will respond, ‘We understand, but you don’t know what it is to be black in this country every day, to be stopped driving through Oakwood, to be followed in a retail establishment just because somebody thinks you’re black so you’re obviously going to shoplift.’”

The civil rights issues of today, Rice said, aren’t about where you can live, go to school, or eat.

“It’s the state of public education, it’s the criminal justice system, it’s housing, it’s banking, it’s social services, a thousand other things,” he added.

In his interview with The Observer, the federal judge said the biggest failure of his professional career has been his inability to work out a consent decree to increase the number of minorities in the police and fire departments.

“And it hasn’t improved,” Rice said. “It’s not that black police officers would cut people in the neighborhoods a break, it’s just that they understand the context in which some of these things are happening, and could better deal with them, and could educate their colleagues on what it is they’re policing in different neighborhoods.”

Baker, who was Fifth District police commander on Salem Avenue in the 1980s — and served as a consultant to Cincinnati after its 2001 race riots — agreed.

“If you look today at some of the major complaints filed by the Department of Justice, we still don’t have the appropriate minority hiring in law enforcement. You’re still looking at the same bleak economic conditions for a certain subset of people. You have unresponsive government in the eyes of some people. That’s what’s so troubling: we’re repeating that cycle, except today, under the glare of all the social media and the 24/7 news.”

Rice said Dayton’s city charter is the obstacle toward diversifying its police department.

“It requires that a promotion list be established every several years that should be ranked on this promotion list on the basis of your score on the civil service exam and one or two other things, “ he said. “And that it’s the rule of one: you must pick the next name on the list for a promotion or appointment.

“You may have someone who scores 100 on the civil service test who doesn’t have the common sense to come in out of the rain. But if you could pick between the top five, you might find someone who scored a 90, yet has street smarts, common sense and the like.

“We don’t have that ability. And because we don’t have it — the city charter doesn’t allow that flexibility — we’re never going to raise those numbers greatly. There has not yet been the political will to do it.”

The judge cites a police community relations meeting he attended nearly a year ago to illustrate his point.

“The police attitude was, ‘Here’s why we do what we do, and if you people would just cooperate, we could keep you safe.’ The black response was, ‘How can we cooperate with you when you treat us like an occupying army?’ And the white police officers said, ‘Well, that’s ridiculous.’”

Rice said American society needs “Jewish, non-Jewish, whites and blacks to get to know each other’s history, background, and perceptions. And I guarantee you that if we do, then a lot of these problems can be resolved.”

“I’ve seen it all,” retired Dayton NAACP President Jesse Gooding said. “I know what discrimination is. That’s why I’m so scared now, man. I am frightened of Trump. Trump is dangerous. I’m scared if he loses, I’m scared if he wins. You know why I’m afraid if he loses? These people will follow him to start a race war. There are a lot of people who are mad.”

“I think Jewish people have a role to play,” Rice said. “Other groups are sufficiently comfortable and sufficiently unknowing — not uncaring but unknowing about the civil rights issues of today — that they’re not going to take the lead in it. How can we do less than continually try to improve the human condition?”

Part One – 50 years after the Dayton riots.

Part Two – The attempt to desegregate.

To read the complete November 2016 Dayton Jewish Observer, click here.