Their blood cries out

More than 100 years ago, five Dayton girls and young women were strangled and raped. Brian Forschner says he knows who did it.

By Marshall Weiss, The Dayton Jewish Observer

Brian Forschner descends the hill to the back edge of Beth Jacob Cemetery on Old Troy Pike. He finds the modest headstone he is looking for in the last row, just before a tree-lined drop.

The Hebrew on the stone is all but worn away, the name on top barely discernible in English: Anna Markowitz.

“This is now one of the prettier spots,” Forschner says of the site.

When 18-year-old Anna was buried here on Aug. 14, 1907, one reporter described it as “the most dismal spot of the dismal little cemetery.”

Thousands attended the funeral of this daughter of Polish-Jewish immigrants. Anna and her parents had arrived in Dayton from Covington, Ky. just two months before.

On the night of Sunday, Aug. 4, Anna had been strangled and then raped at McCabe Park.

With little to go on, police initially arrested her sister and two brothers; they were permitted to leave jail to attend Anna’s funeral.

Newspapers across the United States and overseas reported on the case.

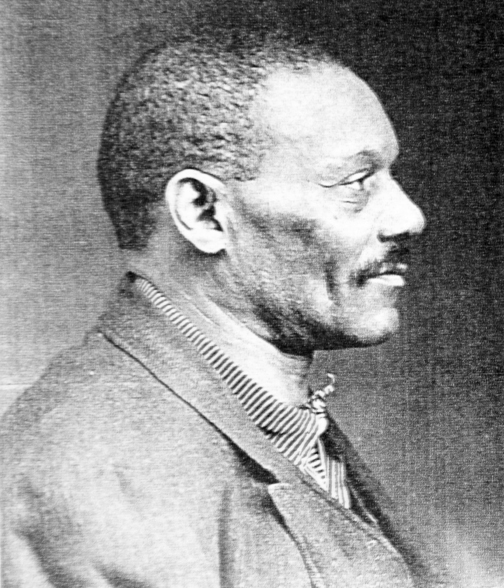

Two months later, three elected officials — the county prosecutor, sheriff, and coroner — sweated a confession out of a man from Dayton’s black community in Tintown, Layton Hines, who today might be described as developmentally disabled.

On trial, Hines recanted his admission of guilt; he claimed the officials threatened to send him to the electric chair unless he confessed. Hines was sentenced to life imprisonment.

But Forschner, who has a background in criminal justice, says Dayton police weren’t convinced of Hines’ guilt.

Two females in Dayton had already been strangled and then raped — 11-year-old Ada Lantz in 1900 and 19-year-old Dona Gilman in 1906. After the Markowitz case, two more would be strangled and raped in Dayton — 18-year-old Lizzie Fulhart sometime between 1908 and ‘09, and 15-year-old Mary Forschner in 1909. These four other cases would go unsolved.

Mary was Brian Forschner’s great-aunt. His research into her murder led him to the stories of the four other girls. Forschner is certain a serial killer was responsible for the girls’ brutal murders.

And he believes it was Temple Israel’s janitor who did it.

And he believes it was Temple Israel’s janitor who did it.

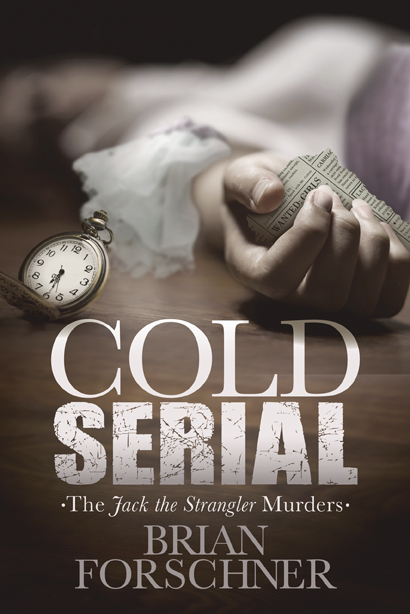

Forschner convincingly lays out the evidence in his book, Cold Serial: The Jack the Strangler Murders, which was released on Oct. 6.

(Full disclosure: I helped Forschner in his research about Dayton’s Jewish community during the time period he covers in Cold Serial.)

As part of the JCC Cultural Arts & Book Fest, he’ll lead two bus tours to the crime scenes, on Sunday, Nov. 15, to show how he arrived at his conclusions. The 2 p.m bus is sold out; tickets are still available for the 4 p.m. tour.

Joining him for the tours will be attorney David Greer, to offer historical context, and actor Scott Stoney, who will provide a voice from the time period.

Stoney portrayed one of Hines’ defense lawyers when Dayton History reenacted the Anna Markowitz murder trial as part of its Old Case Files performances at the Old Court House in 2013.

“You’re going to hear the actual headlines the day these things were announced,” Forschner says of the bus tour, “and you’ll get a sense of how this serial killer operated.”

The term serial killer didn’t exist in the first half of the 20th century. The Western world was familiar with Jack the Ripper’s killings in London in 1888 but little was known about the nature and patterns of such murders and murderers.

“Forensics was in its infancy,” says Forschner, who holds a master’s degree in corrections and education, and a Ph.D. in human behavior/public administration.

A native of Dayton who makes his home in Cincinnati, Forschner has taught criminal justice classes at the University of Dayton. He is also retired from his position as president of senior health and housing services for Mercy Health Partners.

In the first decade of the 20th century, fingerprinting wasn’t yet common in police use across the United States. Blood typing was also in its infancy.

“If a person didn’t confess, or you didn’t see him do it or there wasn’t circumstantial evidence, there wasn’t anything to do,” Forschner says.

Serial murders, he says, were not unique to Dayton at that time.

“Dayton was just massively growing, from about 70-80,000 in 10 years to about 150,000, and people of all languages, all ethnicities, moving in.”

In this booming industrial city, where anyone who wanted employment could find it, young women worked all three shifts in factories such as NCR or toiled at rolling cigars.

The city of Dayton couldn’t keep up with such basic needs as a large enough police force and adequate street lighting.

Young women came and went to work in Dayton via trolley lines from their homes outside the city limits at all hours.

At first, Forschner says, these Dayton murders were covered nationally and internationally in the press because of their sensational nature.

“The media was already hyped because of Jack the Ripper, Robert Louis Stevenson’s Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde, Edgar Allan Poe’s Murders in The Rue Morgue (with an orangutan that murders with a razor blade), Sweeney Todd penny dreadfuls,” he says. “A lot of criminals were described as man-gorilla, fiends, apes.”

These images only further inflamed the racism of the times.

“If there was a crime, particularly a rape, they (Dayton police) would roust the black community,” Forschner says.

After Hines’ coerced confession to the murder of Anna Markowitz, the Rev. J.G. Robinson of the Eaker Street A.M.E. Church railed from the pulpit, “The mistake of one white man is laid at the door of the individual making the mistake; the mistake of one Negro is charged up against the whole race.”

By the time of the Markowitz murder, crime reporters from outside of Dayton who were assigned here noticed patterns that led them to conclude one person had strangled and raped the girls. Two years later, after the Forschner and Fulhart murders, the superintendent of Cleveland State Hospital publicly agreed with this theory.

In newspapers around the country and abroad, Dayton then garnered a reputation as a dangerous place for young women because a monster — “Jack the Strangler” or the “Dayton Strangler” — was on the loose.

Dayton’s criminal justice system dismissed the notion of a single killer. Forschner says this might have been since little was known about the nature of serial killers.

More likely, he says, Dayton’s leaders chose not to pursue the serial killer theory for fear that it would prove even worse for Dayton’s reputation.

“With NCR threatening to leave (1906) and the Wright brothers in the news (1909), Dayton did not want these cases in the news,” he says. “There was a lot of thought that it was in Dayton’s best interest to sweep this under the rug.”

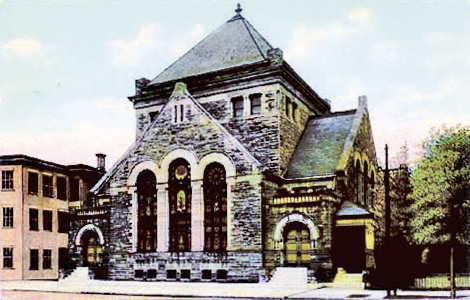

The string of murder-rapes of girls and young women in Dayton ended with the incarceration of Hick White, the janitor at B’nai Yeshurun synagogue, now known as Temple Israel.

White had lured 25-year old Bessie Stickford of Springfield to B’nai Yeshurun on Feb. 2, 1910 with the promise of a job interview. He raped her at knife point in the rabbi’s study.

Exactly a year before, Lizzie Fulhart’s corpse had been found in a cistern in an alley behind the synagogue.

Bessie survived White’s assault and identified him. White was convicted, and imprisoned — only for Bessie’s rape.

Between his escape from the Ohio Penitentiary in 1912 and White’s return to prison in 1922, two girls in Cincinnati disappeared and one was bludgeoned and raped.

Forschner believes White was culpable in most if not all these cases, and more unsolved murder-rapes of Cincinnati girls.

“He was a predator and had been arrested in Dayton (previously) a number of times,” he says. “He was doing predatory things with young girls. He tried to pull a girl through a grandstand.”

In many ways, Cold Serial is a yin to the yang of David McCullough’s bestselling new book, The Wright Brothers.

Dayton prides itself on the spirit of innovation that came out of that first decade of the 20th century.

In the same place and time, Cold Serial paints a portrait of a crisis that brought out the worst in Dayton’s citizens and public servants on the whole.

In composite, government, media, private detectives, and even neighbors seemed more motivated by pride, greed, politics, one-upmanship and grandstanding than the pursuit of anything close to justice.

The JCC’s Cultural Arts & Book Fest will present author Brian Forschner leading a bus tour about the crimes featured in Cold Serial, on Sunday, Nov. 15 at 4 p.m. (the 2 p.m. bus tour is sold out). Tickets, which include a copy of the book, are $20 and are available at jewishdayton.org, by calling 610-1555, or at the Boonshoft CJCE, 525 Versailles Dr., Centerville.

To read the complete November 2015 Dayton Jewish Observer, click here.