The attempt to desegregate

Part Two: Black/Jewish relations from the Dayton riots through desegregation

A Three-Part Series

By Marshall Weiss, The Dayton Jewish Observer

Even before Melissa Sweeny began high school at Colonel White in 1970, she heard about tensions in the building between white and black students.

“There were what they were calling riots,” she recalled. “I can’t say that it was full-blown riots. But it was definitely turbulence in the schools, where the kids would be fighting.”

She remembered her mother, Elaine Bettman, telling her to get inside because a crush of high school students was running down the street.

“And we were a good mile from school,” she said of their home on Harvard Boulevard, across from United Theological Seminary in Dayton View.

“When I was in high school, I remember the same kind of thing happening, and I had to escape into a doctor’s office on my way home,” Sweeny said. “And there was a day when stuff was going on in the high school, and someone lit a girl’s Afro on fire. And she’s running through the halls with her Afro on fire.”

In the years after the West Dayton riots of ‘66, ‘67, and ‘68 — and the destruction and exodus of several businesses along West Third Street — those in the black community who could afford to move elsewhere did so.

One area that wasn’t restricted to minorities was Dayton View, the neighborhood where most of Dayton’s Jews lived at that time.

Individually and as a community, Dayton’s Jews supported integration and the formal process to desegregate Dayton Public Schools.

But as the desegregation order was carried out, the quality of public education in the district declined overall. With crime and vandalism at their doorsteps, Jews were not immune to white flight.

“There were an awful lot of disciplinary problems. People weren’t used to getting along,” said U.S. District Judge Walter H. Rice, whose children attended Dayton Public Schools at the time.

“I remember my older child being afraid to go to school,” Rice said. “There was an arts program that served as a magnet school. It brought people from all over the community, and my son in fifth and sixth grade was simply afraid to attend, not because of the black students and not because of the white students, but because there was so much black-white tension and fights that he simply didn’t want any part of this.”

Mike Emoff lived three houses down from Fairview High School. In 1974, when he was a sophomore, he remembered Dayton started a busing program.

Halfway through his high school years, Emoff’s parents didn’t want to disrupt his education. Though his younger brothers would attend The Miami Valley School, a private, non-sectarian prep school in Washington Township, he remained at Fairview, with approximately 15 Jewish kids in his grade.

“It was probably one of the best things that happened to me personally because I learned how to deal with a world that wasn’t all perfect,” Emoff said. “My parents went to Fairview, my grandparents went to Fairview. It was mostly Jewish at one point. And it’s gone today.”

At Colonel White, Sweeny said there wasn’t busing, since the student body was already integrated, nearly 50-50 by the time she graduated. Four or five of her classmates were Jewish; most Jewish students went to Fairview in Dayton View or to Meadowdale in Northwest Dayton.

“The white kids that didn’t want to be with the black kids had their side of the high school,” Sweeny said of Colonel White. “They hung out on Wabash. And then you had the black kids, who were hanging out in front of the high school, and they never mixed.”

Sweeny said she was part of a middle group that went either way.

“There was actually a group that I started talking to about that — there were probably about 25 of us — to go on little mini retreats,” she said.

“The thought was if those of us that were involved in this could spread it to the rest of the school, then maybe it would calm things down,” Sweeny said.

“Of course that didn’t work, because there were too many opinions on how this should be going. The white kids that were on the Wabash side were not interested in becoming friends with the black kids, so that really wasn’t going to go anywhere. We really thought we were going to be doing something, but it didn’t help anything.”

Emoff said he was pretty close with the dozen or so Jewish students in his grade at Fairview.

“We had that Jewish connection, so we were in that tribe-ish kind of mode, I suppose,” he said.

As Fairview students were bused out and students from other neighborhoods were bused in, they formulated their own tribes as well.

“They had their tribe from Roosevelt, guys that knew each other and they came in and we were taking their turf,” Emoff said. “All the Jewish guys stayed on the sidelines and didn’t get in the middle of any race relations stuff. It was kind of an opportunity for me to learn how to deal with a lot of different kinds of people. I was friends with the new kids, I was friends with the old kids, I wasn’t intimidating to anybody.”

Gwen Nalls, a lawyer and realtor, grew up on Dayton’s West Side. She recalled that as a black girl in Dayton’s public school system, her second-class education ill prepared her for higher education. Nalls graduated from Dunbar High School in 1972.

She and her husband, Dan Baker, are the authors of Blood in the Streets: Racism, Riots and Murders in the Heartland of America, which chronicles Dayton’s racial struggles from 1966 through 1975.

“My teachers would talk to us, not necessarily as a class. They would tell me that at Belmont they have these kinds of labs, they have these kinds of instruments, they have these kinds of resources,” Nalls said. “And then you come over here and you get hand-me-downs if you have anything. There was always this dual system.

“What really manifested itself was when you went to college, when you had to do entrance exams, when you have to try to compete or even keep up, you realized, we never had that. We weren’t taught that.”

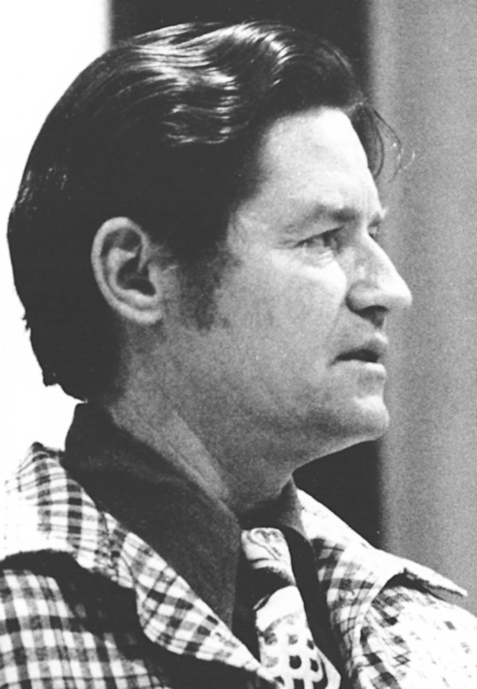

In the late ‘60s, Dayton’s school board and its superintendent were at odds. Superintendent Wayne Carle was an active champion of desegregation. The school board was not.

As a way to help keep a watchful eye — and the peace — at schools that were experiencing natural integration, Carle recruited a network of mothers to volunteer as teacher’s aides.

Among them was Joan Knoll, through the Council of Jewish Women.

“There was an African-American group that was analogous to the Jewish women,” Knoll said. “A lot of people didn’t like us because we were too close to Wayne Carle,” she said of the Jewish mothers who volunteered in the schools. “Because we were too liberal and he was too liberal.”

Frustrated with Dayton’s segregated schools, minority families and the Dayton Chapter of the NAACP filed a federal suit against the district in 1972.

U.S. District Court Judge Carl Rubin initially approved the Dayton plan to bus students voluntarily for limited sessions at environmental science centers.

“It wound up being a good move, even though it was not intended to be that,” said Dayton City Commissioner Jeff Mims of the initial science centers.

Mims began his career in 1970 in Dayton as a teacher’s aide through a Model Cities program.

“They were looking for minorities who lived in the community and who were veterans to become potential teachers, because it was evident at that time that Dayton Public Schools did not have a high number of minority teachers, and the number of minority students was increasing.”

In 1973, Mims was hired to teach art in relation to science at an environmental science center at Eastmont Elementary School.

“The students got a total of 16 days per year in that environment,” he said. “The first year, we had some challenges. We had a group of parents from Ruskin School (on Dayton’s then Appalachian East Side) that actually came to Eastmont attempting to shake the bus. They got carried away and slowly they were about to turn the bus over, and then one parent said, ‘Oh! The kids are still on the bus.’ And so they stopped for that reason.”

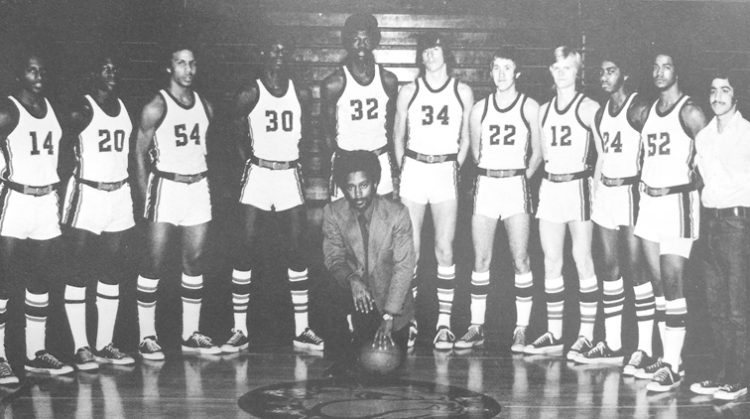

When Mims was assigned to teach social studies at Belmont High School, he already knew 80 percent of the students — black and white — since he had taught them at the science center as elementary school students.

“I ended up in a situation where the kids would be fighting or doing some crazy things,” Mims said, “and I’d walk up to them and ask them to stop, and they’d look up and say, ‘OK, Mr. Mims.’ And the principal said to me, ‘Who the hell are you?’”

The NAACP appealed Dayton’s limited magnet approach and the plan was eventually deemed insufficient. By the summer of 1975, Rubin assigned Ohio State desegregation expert Dr. Charles Glatt to devise and implement a comprehensive desegregation plan for Dayton.

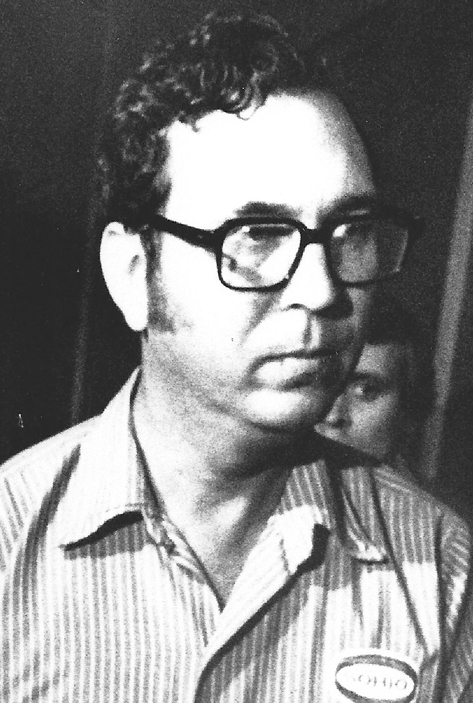

Irate at the thought that his children on the white East Side of Dayton would be bused to go to school with black children, racist Neal Bradley Long had begun his killing spree in the summer of 1972, randomly shooting blacks on the West Side in the early hours of the morning.

For the next three summers, he would continue to shoot at least 30 black men, killing seven.

When Glatt was assigned to desegregate Dayton’s schools, Long killed him at point-blank range in his Dayton office. It was Dan Baker, a Dayton police officer at the time, who took Long’s confession to 30 previous shootings.

Glatt’s murder, Mims said, gave the mission of desegregation more purpose.

When Dayton’s NAACP needed to raise $60,000 for its legal fees connected to the 1972 federal case, Lou Goldman, president of the Jewish Federation of Greater Dayton, helped organize the fund-raising, recalled Jessie Gooding, Dayton NAACP’s former president, who was NAACP vice president at the time.

“Lou was always friendly to the NAACP,” Gooding said. To assist with the federal case, NAACP’s national office had a cadre of lawyer volunteers who were Jewish.

“The national director of the NAACP at the time, you could call him in the morning and that evening, with no money, he’d have a lawyer in Dayton,” Gooding said. “I can remember three or four Jewish guys he sent down here. He’d send them to Dayton, overnight.”

Before the federal appeals court insisted that Dayton Public Schools get on the track to real desegregation, members of Dayton’s Jewish community were actively involved in trying to get levies passed and desegregation-friendly candidates elected to the school board.

One of those who ran in 1973, unsuccessfully, was Ellen Faust.

“By then, the school board had a large representation of people who were for segregation and the continuation of it,” Faust said. That side called itself Save Our Schools, SOS. The business community in town formed a group called CBS, Citizens for Better Schools.”

A key desegregation leader in the Jewish community at that time was Carol Pavlofsky.

“She was just out there recruiting women,” Knoll said. “She had a crew of women reporting to her.”

Peter Wells, retired executive vice president of the Jewish Federation of Greater Dayton, arrived here in 1973 as assistant to the Federation’s executive director.

“Where we were mostly involved in the desegregation process was as observer members of the Metropolitan Churches United, the interdenominational organization,” Wells remembered. “The churches took a role in trying to pull the community together: corporate, labor, the religious community, the non-profit community, the black community, and the police. Church leaders went to the corporate people and said, ‘You may live in Oakwood but you work in Dayton. If Dayton burns, you burn.’ And that led to a peaceable segregation.”

“I knew what they were feeling,” Baker said of the Jewish community.

“When the big fights would happen at Colonel White all those years ago, a lot of Jewish families lived right there on all those streets around there,” said Baker, who lived in Dayton View at the time.

“It was a shame. And they spoke out, wanting and trying to lead peaceful resolutions to those things, and put tremendous pressure on the school board and the police department, as they should have, to try to come to some resolution.”

“We had rallies and we had meetings,” Joe Bettman said. “We once rented a yellow school bus and they had a parody song of Yellow Submarine, and we’re all in this yellow bus, going around the neighborhood, trying to rally some support.”

Desegregation activists weren’t just going for Dayton’s schools; they attempted to convince suburban districts to become part of the plan. They knew it was the longest of longshots.

Joe Bettman was invited to a Kettering PTA meeting to debate a vice president of the Kettering Board of Education about the pluses and minuses of desegregation.

“The hall was filled,” Bettman said. “Well, they really gave me a hard time, and a few shouts here and there.”

If there were Jews who didn’t support desegregation, they kept it to themselves.

“Jewish leaders knew what it was like to be disenfranchised and second-class citizens in the eyes of many,” said Robert Weinman, an assistant superintendent of Dayton Public Schools when desegregation took place. “So how could we, with our backgrounds and our history stand in the way?”

“A lot of the young people who were from the area where a lot of Jewish families lived, they were more amenable and understanding in accepting the different cultures,” Mims said.

Even so, there were incidents. But incidents brought the potential for teachable moments.

When one of his Jewish students disrupted his class, Mims told her to move her seat. At first she refused.

“I said, ‘move to this location,’ and so, as she picked up her books to move, she said, ‘black f—er.’ I took my pen out and I’m saying this out loud to the whole class as I’m writing her up, ‘I asked student to move to newly assigned seat. In the process of moving, she called me a black f—er.’ I said to her, ‘Here, take this to the office.’”

She returned to school after her three-day suspension when Mims’ class was creating jewelry.

“And so I sit down with her, I was working with her because she was making this necklace and earring set that she wanted to wear to the prom,” Mims said. “And all the kids are looking, because they think I’m going to be mad at her. And so we got along fine. And after about three days, she apologized. She said, ‘I’m really sorry.’”

At Fairview High School, Emoff recalled trouble that came “from all the white jocks who were there. They were competing for different status levels at the school, like the football team and the basketball team.

“Some of the white kids that came in came from the North Dayton area, the rough white kids were the ones who were bumping heads with the black kids.”

Emoff said some students were killed in the fights.

“Somebody shot himself in my back yard,” he said. “It was a white guy who was just depressed because he was stressed with school. There were five suicides, black and white, in those last two years, not all at school. And there were a lot of drug-related things that were happening at school.”

Emoff and other honors students at Fairview were bused three afternoons a week to participate in the district’s high school honors program, at the YMCA downtown.

“Fairview had dropped its honors programs, because that wouldn’t have achieved the objective within the school,” he said.

Another dimension to Emoff’s perspective was the kidnapping and murder of his grandfather, furniture store owner Lester C. Emoff in 1975.

“My grandfather was kidnapped by three black guys, one of whom is still alive and still in prison; the other two have died in prison. And they shot and killed him. That did not sit well with me, obviously. But I didn’t let that seep into anything at school. I just kind of stayed to myself.”

Along with other members of the middle class, the Jews began moving out of Dayton View to Northwest Dayton, suburbs north of Dayton, and a few to areas south of town, for an amalgam of reasons.

“Kids would start stealing their bikes,” Dr. Charlie Knoll said when he and his wife began thinking of moving. “Aaron got a new bike, someone stole it off the front porch. We had a Thunderbird. People came along and threw bricks through the windshield.”

Weinman said some families that chose to remain in Dayton boosted enrollment at private schools such as The Miami Valley School and Hillel Academy Jewish day school.

“As I look at my fellow religionists, we’re a strange group,” Weinman said. “We’ll give our money, in fact sometimes we’ll give even our life to help. But when it comes to our own families, we want the best education for our youngsters. Because of deseg, you’re bringing in a less well-educated group, which can (academically) harm those that are ahead.”

Nalls said white flight was a self-fulfilling prophecy. “The schools are going down, and when you pull your kids out, yes, it went down.”

“I can relate to what their feelings were,” Baker said of the Jews of Dayton View, “the mixed feelings about being in an area you feel is a progressive area, an accepting area. That’s what Dayton Triangle was clearly all about. I have to admit, I was a real sucker for believing all that for a long time too — the urban pioneer. Until my house was broken into twice, my car stolen three times, and my teenage daughter was abducted at gun point by a drug addict at her morning school bus stop in ‘84. Thank God she was recovered by police five hours later. I said, that’s enough. Get out. So you say to yourself, ‘How much social consciousness do you have?’ But what you do is protect your family.”

Part One – 50 years after the Dayton riots.

Part Three – What we did and didn’t learn.

To read the complete October 2016 Dayton Jewish Observer, click here.