50 years later

Black/Jewish relations: from the Dayton riots through desegregation

Part One of Three: 50 Years Later

By Marshall Weiss, The Dayton Jewish Observer

“It was bound to happen” was the headline of Anne M. Hammerman’s column on Sept. 8, 1966. The editor and general manager of the Dayton Jewish Chronicle wrote that city leadership “was alerted to a possible riot weeks earlier.”

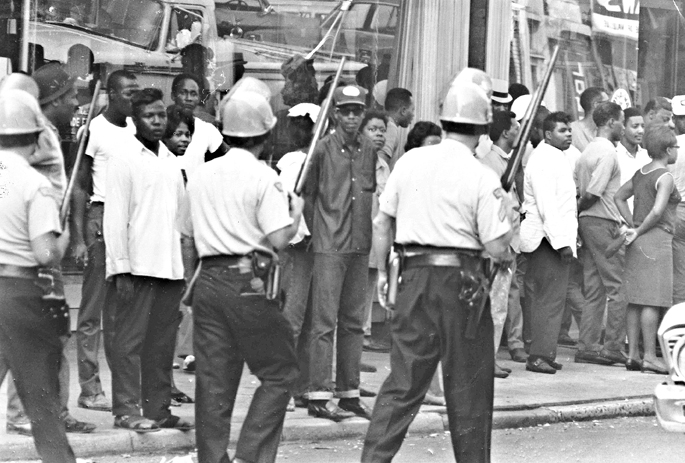

In the early morning hours of Sept. 1, 1966, a white man fired a shotgun out of his car window and killed African-American Lester Mitchell on West Fifth Street.

The event, which appeared to be a random drive-by shooting, triggered the worst riot in Dayton history.

A thousand National Guardsmen were sent to the lower West Side of Dayton, where they remained for five days.

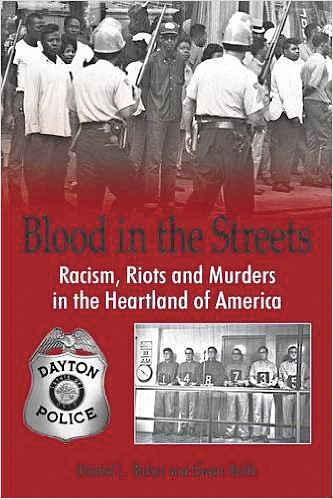

“It just tore the city apart,” said Daniel L. Baker, who was a police officer stationed on the West Side when the ‘66 riot broke out. Baker and his wife, Gwen Nalls, are the authors of the 2014 book, Blood in the Streets: Racism, Riots and Murders in the Heartland of America, which covers the period of 1966 through the desegregation of Dayton Public Schools in 1975.

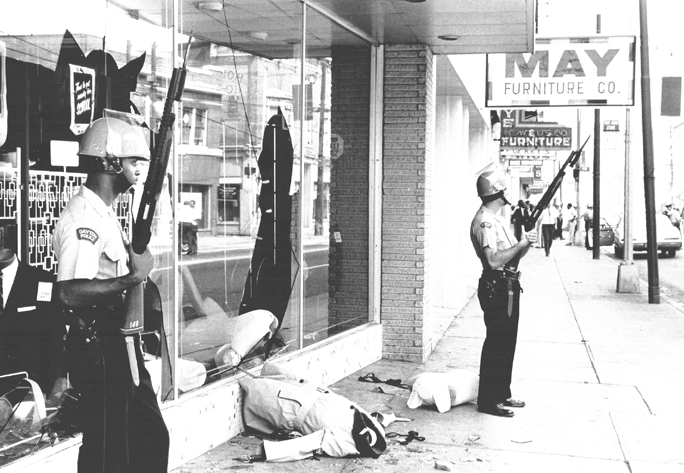

“The area was burned out,” Baker recalled of the vandalism, fires and looting that ensued in the rioting along West Third Street, the retail center of Dayton’s predominantly black West Side. “Many merchants never came back. And many of them were Jewish owners. After 1966, the city was in pretty significant disarray.”

Bruce Brenner was 17 when the first riot hit West Dayton. His parents owned a grocery at West Fifth Street and Western Avenue.

“After a couple of days, we went back in there because there was meat and produce we had to go through,” Brenner remembered. “Our store did not get any damage. Basically, the general consensus through the residents of the neighborhood was, that for the merchants that treated the people fairly, they saw that when troublemakers came into the area, they helped protect those businesses and kept people from damaging them.”

Another Jewish business owner, with a shop on West Third Street at the time of the ‘66 riot, concurred.

“I had no loss during the insurrection,” said the business owner, who requested anonymity. “I had some customers stand in front of my place and said not to touch it. Police asked me to board up the windows. My only expense was the plywood.”

He added that though it took a while for business to get back to normal, he didn’t think about leaving.

That some Jewish businesses were vandalized and looted on the West Side knocked the Jewish community off balance.

Since the beginnings of the civil rights movement, Jewish communities across the United States — including Dayton’s — were vocal supporters of the cause.

Jews were among the founders of the Dayton Urban League, including Temple Israel’s Rabbi Selwyn Ruslander; and in 1958, Dayton’s Jewish Community Relations Council officially endorsed desegregation and fair housing.

That same year, Dayton’s Jewish Community Council (predecessor to the Jewish Federation) reported in its newsletter that “community members have been receiving ‘hate literature’ of the most vile form…to convince the reader that Jews are the power behind the movements of Negroes for equal opportunity.”

That same year, Dayton’s Jewish Community Council (predecessor to the Jewish Federation) reported in its newsletter that “community members have been receiving ‘hate literature’ of the most vile form…to convince the reader that Jews are the power behind the movements of Negroes for equal opportunity.”

Dayton’s JCRC, chaired by Dr. Louis Ryterband, coordinated early lobbying for the 1964 Civil Rights Bill.

“I thought there had always been a very healthy, respectful relationship between Jewish people and African-Americans,” said U.S. District Judge Walter H. Rice, who arrived in Dayton in 1962. “Jewish people were present at the founding of the NAACP, marched with King, and were civil rights activists,” he said. “I kept reading and kept being told that a lot of the Jewish people who had run retail establishments — not only in West Dayton but throughout the country — used to exploit their black customers. The Jewish people were shocked: they had tried so hard to be good landlords, good shopkeepers.”

Rice, who was then in private practice here, recalled a Jewish businessman from the West Side who told him that he had a long list of debtors, people who owed him money, “because he carried those people through bad times, and he was shocked to find out that they felt he was a racist.”

Hammerman expressed concern about these negative Jewish stereotypes in the pages of the Jewish Chronicle: “There may have been a few here and there who milked their customers of a higher rate of interest — but by and large, our people have done much to elevate the West Side of Dayton and they do not deserve these false accusations.”

“I think from then on,” Rice said, “there has been a feeling of wariness between the two groups. Just like a friendship, you feel that you are simpatico with someone, and then all of a sudden you find that each of you retains deep suspicions and distrust about the other. So I think it has changed. Not permanently, not beyond repair. But it put a burden on the relationship.”

Blood in the Streets author Daniel L. Baker, whose family migrated here from Kentucky, grew up on the predominantly white East Side. His wife and co-author, attorney and realtor Gwen Nalls, grew up on the West Side. Nalls is black, Baker is white.

The title doesn’t just refer to the riots in Dayton of ‘66, ‘67, and ‘68: it follows the murders of serial killer Neal Bradley Long from Dayton’s East Side, whose random shootings of black men on the West Side in the summers of the early ‘70s ratcheted up community tensions even higher. In 1975, Long would kill Dr. Charles Glatt, the desegregation specialist hired by Dayton Public Schools to oversee integration of the district.

Though never proven, Baker is convinced it was Long who killed Lester Mitchell in ‘66, which sparked the first riot.

“I grew up in the middle of all this,” Nalls said. “My parents are from Mississippi. They migrated here for work. When they came to town, General Motors was here, every major industry was booming. My mom was a day worker. She went to work for a Jewish family, cleaning their home.”

Baker observed that the migration pattern of blacks and whites coming to Dayton from the south for jobs — with whites on the East Side and blacks on the West Side — only solidified the segregationist nature of the city.

Joan and Dr. Charlie Knoll moved to Dayton in 1956 from northern Ohio. They recalled Dayton as solidly segregated.

“There was an unwritten law that you did not put African-American patients in the same room with non African- American patients,” Dr. Charlie Knoll, a longtime physician said. “And the first hospital to break that was Miami Valley.” He pushed to have St. Elizabeth’s integrated.

Joan Knoll worked as a secretary at the VA hospital, where she befriended women who were African-American. When she would ask them to join her downtown for lunch, they would always decline.

“Finally, I asked, ‘Is it because of the difference of our skin?’” she said. “‘No, we can’t eat lunch at Rike’s. We can’t go to a movie downtown.’ These were professional women. Social workers and so forth. They were upper-class women.”

In 1960, Rice and his first wife — a native Daytonian — were planning their wedding here.

“We had some African-American friends from Pittsburgh that we wanted to invite,” he said. “And my prospective father-in-law called several hotels and was told they couldn’t stay there. And finally, they were accommodated at the Van Cleve Hotel, only because my father-in-law threatened to move the wedding elsewhere; it was scheduled for the Van Cleve.”

Ellen Faust and her parents came to Dayton in 1936, when she was 3 months old. Her father opened a store on West Third Street and the family lived in the back.

She and her husband, Howard Faust, a pharmacist from Cincinnati, settled in Dayton in 1959. Armed with her education degree, she interviewed with Dayton Public Schools.

“Places like Fairview High School were all white, certainly there were no black teachers,” she said. “The assistant superintendent at the time, the head of personnel, interviewed me for the job. And he said, ‘I need teachers at Roosevelt and at Fairview. You wouldn’t want to teach at Roosevelt.’ Dunbar High School was an all-black school, and Roosevelt was a mixed school.”

At Fairview, Faust taught chemistry and general science.

“At one point, a black student who came to register — the family had moved into the district — was told, ‘You’d be more comfortable going somewhere else.’ So there were very deliberate attempts to make sure that black students had only some access, and there was nowhere to go to protest that kind of thing.”

Faust said she became an activist in civil rights when Rabbi Selwyn Ruslander’s daughter, Gail Levin, was president of the League of Women Voters.

“The League of Women Voters did a study of education and looked at segregation in Dayton schools,” she said. “And that was probably the first time that I looked at it seriously.”

For Knoll, it was her work with the Council of Jewish Women.

“The National Council of Jewish Women had a store on West Third and Broadway,” Knoll said. “Dorothee Ryterband ran it. They sold second-hand clothing to people with low incomes.”

She recalled that it was Dorothee Ryterband who saved the store during the ‘66 riot, “when she handed out sodas to the soldiers and the rioters in front of the store. Little bitty Dorothee. She was gutsy.”

Faust also became involved with the Council of Jewish Women.

“The council always had as its basis, social action,” she said. “With that, Council was considered the Jewish group for women that you had to belong to, to be socially acceptable.”

Along with Dorothee Ryterband, Sybil Silverman led the council’s charge on racial justice activities.

A year later, on Sept. 16, 1967, in the midst of a Shriner’s convention in downtown Dayton, a police officer shot and killed an African-American man he thought was carrying a gun. When it turned out to be a pipe, the policeman planted a gun on the man’s body.

Another riot ensued, this time urged on by activists from out of town, such as H. Rap Brown.

That’s when Faust and Knoll started marching, their kids in tow.

“We marched with the rabbis and Protestant ministers, priests and nuns,” Knoll said.

One influential member of the Jewish community told Knoll’s husband that “if his wife kept on doing these things, he was going to lose his practice,” Knoll recalled. “You see, it was hard to talk people into doing what wasn’t fashionable. Ellen and I were bad girls.”

Rioting continued in ‘68 following the assassination of the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.

Since the early 1900s, the Emoff family had a furniture store on West Third Street.

“I remember going to the store pretty frequently with my Dad at 2 in the morning when he got a call that his windows were broken, probably three or four times,” said Mike Emoff. “And we’d go down and meet the police there, and the windows would be smashed in the front. I didn’t understand it. I didn’t know what was happening. I was maybe 8 to 12. Those were the ‘60s, almost ‘70s. It was just out of control.”

Emoff said his family kept the store there in the years right after the riots.

“That’s where they started. My Dad got along really well with the residents of the West Side of Dayton. Even though all that happened, the riots were more of an emotional type of reaction, and it didn’t matter whose store was there, there were people who just looted and smashed. I was young, so I didn’t get a lot of that, but I looked through the news clips I found when my Dad died. Some of that stuff bothered him, obviously. He kept it.”

“I couldn’t understand the riots,” Nalls said. “I couldn’t understand why. I remember hearing it on TV, and I’d ask my parents, what sense does it make for them to be burning down our backyard? And to this day I don’t understand it. Even today, you can go and see it never really got back to what it was.

“Rap Brown and those guys, their focus was, ‘I’m going to get your attention by burning it down,’ which is the Ferguson approach: not only are we not going to support your establishment, we’re not going to let anybody else in.”

Baker described West Dayton in the summer of ‘66 as a tinderbox.

“The Civil Rights Act was passed in 1964, and in the United States it was not well-received in many places,” he said. “And then the Watts riot in California happened in 1965, the worst riot in this nation’s history.”

According to the Associated Press, 43 riots tore across U.S. cities over the summer of 1966, including Chicago, Cleveland, Atlanta, and San Francisco.

Baker recalled that in May ‘66, the Dayton Daily News presented a series called West Side ‘66; it addressed issues of segregation, poverty in the black community, lack of education, and police brutality.

“And guess what? In all of those articles, many of the black leaders of the time predicted this place is going to blow up if we don’t fix some of this,” Baker said. “One guy said if it gets above 95 degrees here this summer, this city’s going to explode.”

Rice remembered that police/community tensions in ‘66 were raw.

“The police, frankly, treated members of the community poorly, with disdain and lack of respect, and were perceived — not in an exaggerated fashion — as an occupying army,” Rice said. “It’s sad to say, but in many areas of the community, while the police tactics changed, the tension still exists.”

Rice found himself on an extradition case in Los Angeles on the next to last day of the Watts riots in 1965 when he was with the Montgomery County Prosecutor’s office. Although he said the Dayton riot of ‘66 was not as bad as Watts, it made indelible changes on our city. And fear on all sides was palpable.

“Within about five years, the neighborhood was almost a ghost town as far as retail overall,” he said.

West Dayton on the whole, Rice said, was fairly integrated then. “Inner West was African-American but Outer West off Third had a lot of white people. So not only did you have the flight of the white middle class, you had the flight of the black middle class as well. And the neighborhood, for about 20 years, was left to die.”

One of the areas where members of the African-American middle class migrated to was Dayton View, then the hub of the Jewish community.

Despite the Supreme Court’s 1954 mandate in Brown v. Board of Education for public schools to desegregate “with all deliberate speed,” Dayton Public Schools all but ignored the order until it was faced with a 1972 suit brought by local families and the NAACP.

As the suit made its way up to the Supreme Court and back to the U.S. District Court, Dayton’s Jewish community would join the fight to desegregate the school system and attempt to keep the atmosphere as peaceful as possible with the most powerful weapon in its arsenal: the Jewish mother.

Part Two – The attempt to desegregate.

Part Three – What we did and didn’t learn.

To read the complete September 2016 Dayton Jewish Observer, click here.