A work in progress

In the news series

Jewish Family Education with Candace R. Kwiatek, The Dayton Jewish Observer

The use of biotechnology and biomedical engineering for human benefit extends back at least 13,000 years, to physical evidence of rudimentary tooth cavity fillings made with a mixture of tar, hair, and plant fibers.

Deliberate holes drilled in skulls from the 7th millennium B.C.E. indicate the use of trepanning, an ancient neurosurgical procedure used for treating head wounds and mental disorders.

A 4,800 year-old artificial eye was discovered in Iran, and archaeology in Egypt revealed a 3,000-year-old functional prosthetic toe. Documented in Egyptian papyri from as early as 1,600 B.C.E. is the use of moldy bread to treat infection and willow bark for pain relief.

Until recently, the human body was regarded with both reverence and practical concern as an entity described by the psalmist as “fearfully and wonderfully made.”

From ancient folk remedies to modern applications of research and technology to the human body, medicine was viewed as a sacred calling focused primarily on physical repair, treating infection and disease, alleviating pain, improving diagnostics, and developing medical devices and processes to approximate or restore normal function and health.

Think pacemakers, noise-cancelling hearing aids, health-tracking smart watches, advanced prosthetics like bionic arms, even gene editing to eliminate disease.

But headlines from this past year alone suggest a very different story about merging technology with medicine:

Transhumanism: the future or the world’s most dangerous idea? Is technology rewriting what it means to be human? How transhumanism dangerously ignores human nature. Transhumanism is not just latest tech advance but seeks to one day replace humans, says panelists. Artificially alive: How AI is bringing the dead back and what that means for the living. Elon Musk’s 2035 Prediction – Humans Will Merge with AI.

These noteworthy snippets are just a sample of dozens of equally intriguing headlines that highlight the increasing integration of science and advanced technology with the human body and mind to fundamentally enhance human physical and cognitive abilities, overcome biological limitations, and even achieve radical life extension.

They also reveal medicine’s evolving view of the human body from a sacred vessel to a complex machine.

These are the ideas embraced by transhumanism, a philosophical and cultural movement advocating for using science and technology to move beyond existing human limitations and cognitive limits in order to fundamentally transform the human condition. According to transhumanism, the human is always a work in progress.

Futuristic ideas do have precedent. Throughout history, humans have tried to transform themselves: to become stronger, gain greater wisdom, overcome limitations, even triumph over death, contemporary philosopher John Philip notes. “(Humans yearn) to become better than (they) are, better than human.”

But the Bible warns against progress that oversteps divine boundaries. In the Garden of Eden, God commanded, “Of the tree of the knowledge of good and evil, you shall not eat.” Later, the snake added, “On the day you eat from it, then your eyes shall be opened, and you shall be as God, knowers of good and evil.”

Instead of obeying the divine prohibition, Adam and Eve chose to eat from the tree and glean this knowledge on their own terms, resulting in God banishing them from Eden.

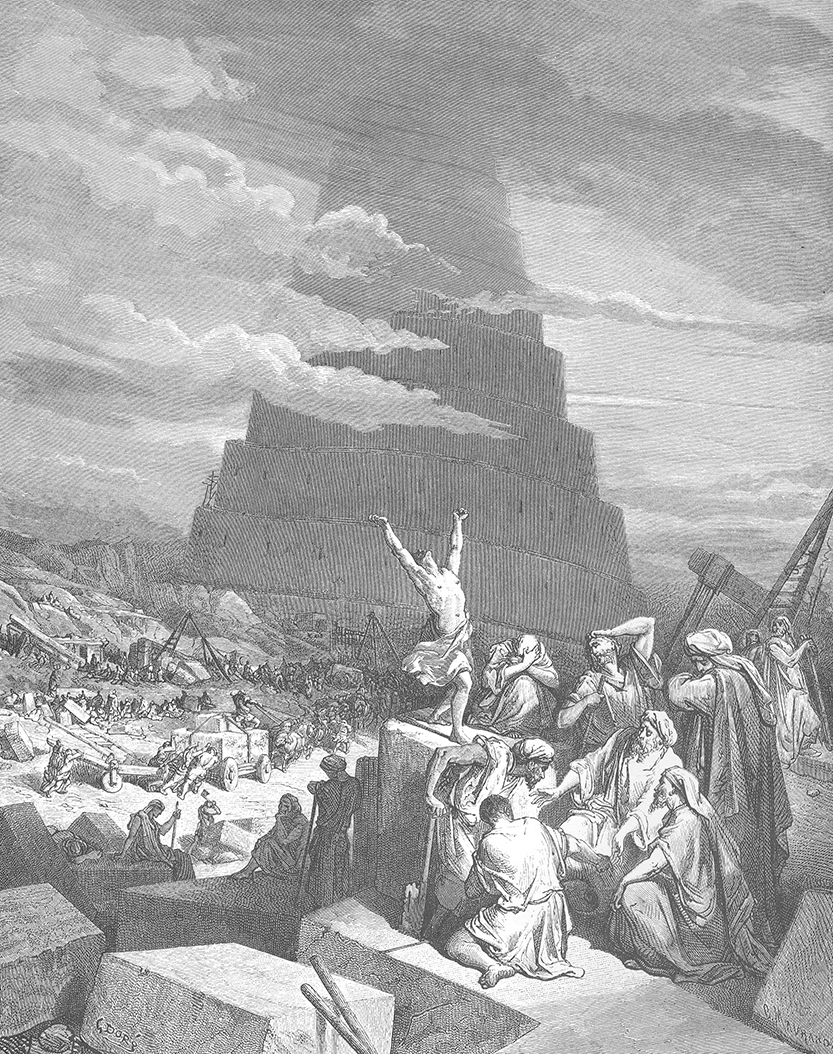

After Noah, the people of the earth settled in Babel where they created bricks and built a city with a tower reaching into the heavens, seeking to make a name for themselves.

This attempt to become their own masters, to live forever through their legacy and technology, led instead to God confusing their speech and scattering them across the earth.

These stories highlight the core tension that lies between transhumanism’s drive to transcend human limits, identity, and even death, and Judaism’s emphasis on accepting human limitations, finding sanctity within the created world, and recognizing mortality as central to a meaningful life.

Both worldviews consider the maxim “the human is always a work in progress” to be a foundational principle.

But for Judaism its meaning encompasses the commitment to personal growth, refining one’s character and behavior, and managing one’s yetzer hara (evil inclination).

Author Serenella Verduchi succinctly expresses Judaism’s perspective: “Man is not a product to be optimized, but a creature endowed with intrinsic dignity, called not to self-creation, but to a relationship with God, with others, and with creation.”

Of course, Judaism does encourage the use of technology to improve the human condition.

Engaging in medicine, science, research, and technology for the purpose of healing are considered holy endeavors, sacred acts of fulfilling the will of God, also known as rofeh cholim (healer of the sick).

But the increasing abilities of technology and medicine raise questions previously unimagined.

Does technological enhancement or alteration diminish or enhance the dignity of the human, created in God’s image?

Is transhumanism a modern form of idolatry, replacing faith in God with faith in technology? How will radical life extension or digital immortality impact the meaning that can be found in the finite, mortal nature of being human?

When does transhumanism overstep divine boundaries? The issue is not technology itself, but whether it serves “divine purpose and ethics” or serves man, becoming an idol.

In 1943 author C.S. Lewis wrote this prophetic warning: “For the wise men of old the cardinal problem had been how to conform the soul to reality, and the solution had been knowledge, self-discipline, and virtue. For magic and applied science alike, the problem is how to subdue reality to the wishes of men: the solution is a technique; and both, in the practice of this technique, are ready to do things hitherto regarded as disgusting and impious — such as digging up and mutilating the dead.”

Literature to share

Ghosts of a Holy War: The 1929 Massacre in Palestine That Ignited the Arab-Israeli Conflict by Yardena Schwartz. Hebron, the burial place of Abraham, is home to one of the world’s most ancient Jewish communities. For centuries, it was a place of peaceful coexistence between Muslims and Jews: until the 1929 Hebron massacre. Inspired to undertake years of historical and on-the-ground research via the extensive writings of a young American Jew living as a yeshiva student in Hebron in the 1920s, Schwartz ultimately concluded, “There is a direct line between 1929 and 2023.” This acclaimed nonfiction work is the highly readable and intensely interesting account of Schwartz’s research journey that explains why she says, “If you don’t understand 1929, you’ll never understand Oct. 7…Everything began there.”

Rembrandt Chooses a Queen by Kerry Olitzky and Deborah Bodin Cohen. Friendly with the Jewish community in 17th-century Amsterdam, Rembrandt van Rijn often consulted Jewish theologians and texts for insights for his biblical scenes. But could his young Jewish apprentice also be of help? Inspired by Rembrandt’s Ahasuerus and Haman at the Feast of Esther, this imaginative historical tale weaves together the story of Esther with art, history, culture, and Jewish values into a delightful picture book for elementary ages.

To read the complete February 2026 Dayton Jewish Observer, click here.