Daytonians and the Holocaust: What did we know? How did we respond?

By Marshall Weiss, The Dayton Jewish Observer

The traveling version of the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum’s Americans and the Holocaust exhibit, on display through June 21 at the Dayton Metro Library’s main library, poses questions to those who take it in — What did Americans know? What more could have been done?

The exhibit’s lead historian, Rebecca Erbelding, has said it challenges people regardless of their preconceived notions.

“If you come in thinking the United States did everything it could to stop the Holocaust, you’re going to get challenged. That preconception will not be with you when you leave. If you think the United States could not have done anything, you’re going to be challenged as well,” she told The Observer in a previous interview.

Here, The Observer looks at what Daytonians knew and how they responded to reports of the Nazis’ atrocities against the Jews.

An examination of local daily newspapers of that time period shows that Daytonians were kept well informed of Nazi Germany’s antisemitic rhetoric, edicts, and actions against Jews under its control, from the rise of the Third Reich in 1933 through the Nazi genocide of more than 6 million Jews by the time of Nazi Germany’s surrender in May 1945.

These news reports, usually from wire services, were presented with frequency and prominence, often on the first page or in the first few pages of the front section of Dayton’s daily newspapers. They were augmented by strong editorials, opinion pieces, and syndicated columns denouncing the actions of Nazi Germany against the Jews of Europe.

If newspaper readers living in Dayton in the 1930s or 1940s claimed they didn’t know what the Nazis were doing, they would have been in denial or willfully ignorant.

Though some in Dayton’s German community showed their support for Nazi Germany and Hitler’s fascist regime, their attempts to organize were short-lived and solidly denounced by the organized German community here.

For its part, Dayton’s organized Jewish community mobilized to provide what relief it could for the persecuted Jews of Nazi Europe. Dayton’s Jews prepared to receive and provide for their share of what would turn out to be the very few European Jewish refugees who could flee and make their way to America.

Germans and Jews in Dayton

Dayton’s YWCA reported in 1910 that the city was home to 5,816 people of German origin and a Jewish population of 4,500.

Eastern European Jews lived in the neighborhood of Wayne Avenue and Wyoming Street in the East End, as did German immigrants and their adult children.

“If you were lucky, your mother gave you a penny, and you could buy a single piece of candy, or better yet, a large, soft pretzel on which you spread thick mustard, at one of the two corner stores — Motzel’s or Schommer’s,” Dayton Daily News sportswriter Si Burick recalled of the old neighborhood of his childhood in a 1971 column. Those corner stores were German-owned.

Burick’s father was the rabbi at Beth Abraham Synagogue, which dedicated its new building at 530 S. Wayne Ave., across from Jones Street, in August 1918. It was then an Orthodox congregation of Eastern European Jews, mainly from Lithuania.

The synagogue had hired Becker’s German Band for the procession to the new building.

“As they approached the edifice built for the preservation of Orthodox Jewish tenets and ethics, the bandsmen proudly burst into an enthusiastic rendition of Onward, Christian Soldiers,” Burick added.

Near Beth Abraham Synagogue, at 610 S. Wayne Ave., stood Liederkranz Hall, the base of operations for Dayton’s celebrated German men’s chorus.

Burick remembered that Jews in the neighborhood would rent Liederkranz Hall for meetings, Yiddish theatre productions, charity balls, and weddings.

Jewish-owned businesses also bought ads in Dayton Liederkranz’s concert series program books. Among them were Cincinnati Bakery, O.K. Bakery, The Metropolitan, attorney Sidney Kusworm Jr., and Israel Brothers Scrap Metal. An ad from Israel Brothers in a 1940 Dayton Liederkranz concert program book notes that “Herman Israel is a member of Dayton Liederkranz.”

Born in Germany in 1868, Herman Israel immigrated to the United States when he was a teenager, in 1883. He would become president of the scrap metal business his father, Benjamin Israel, started in Dayton in 1881.

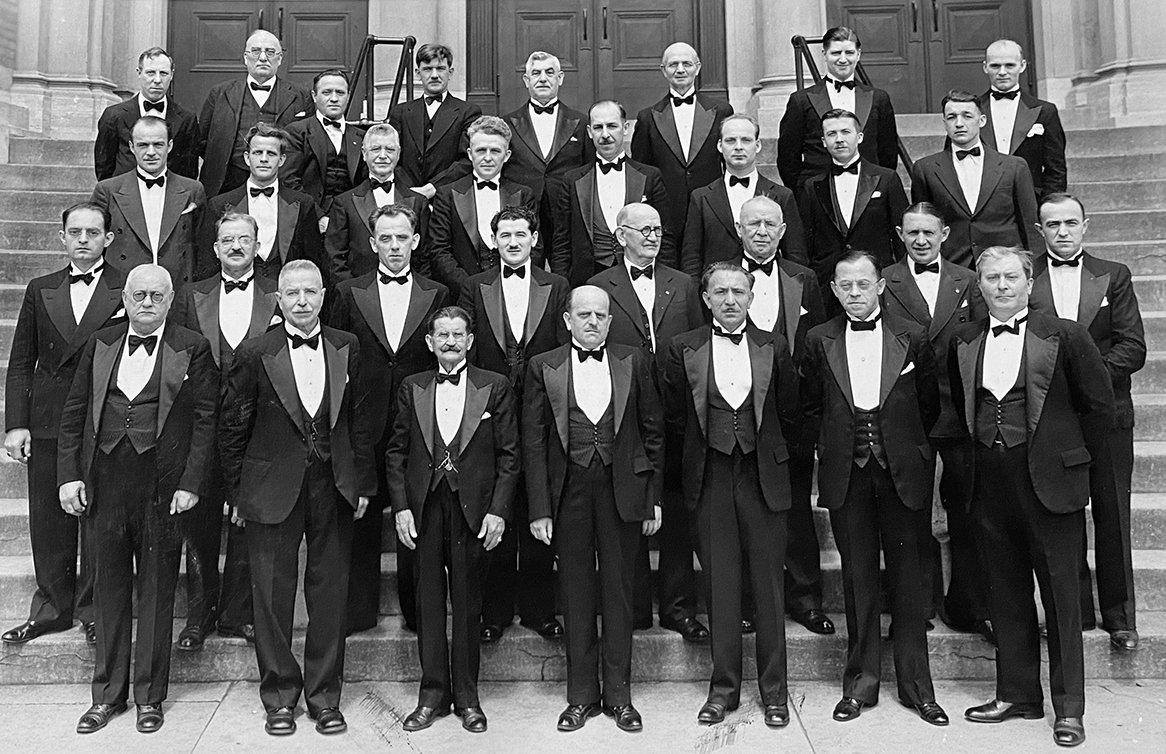

Liederkranz chorus members admired the stately beauty of the new Beth Abraham building. The ensemble began taking its yearly publicity photos on the steps in front of the synagogue.

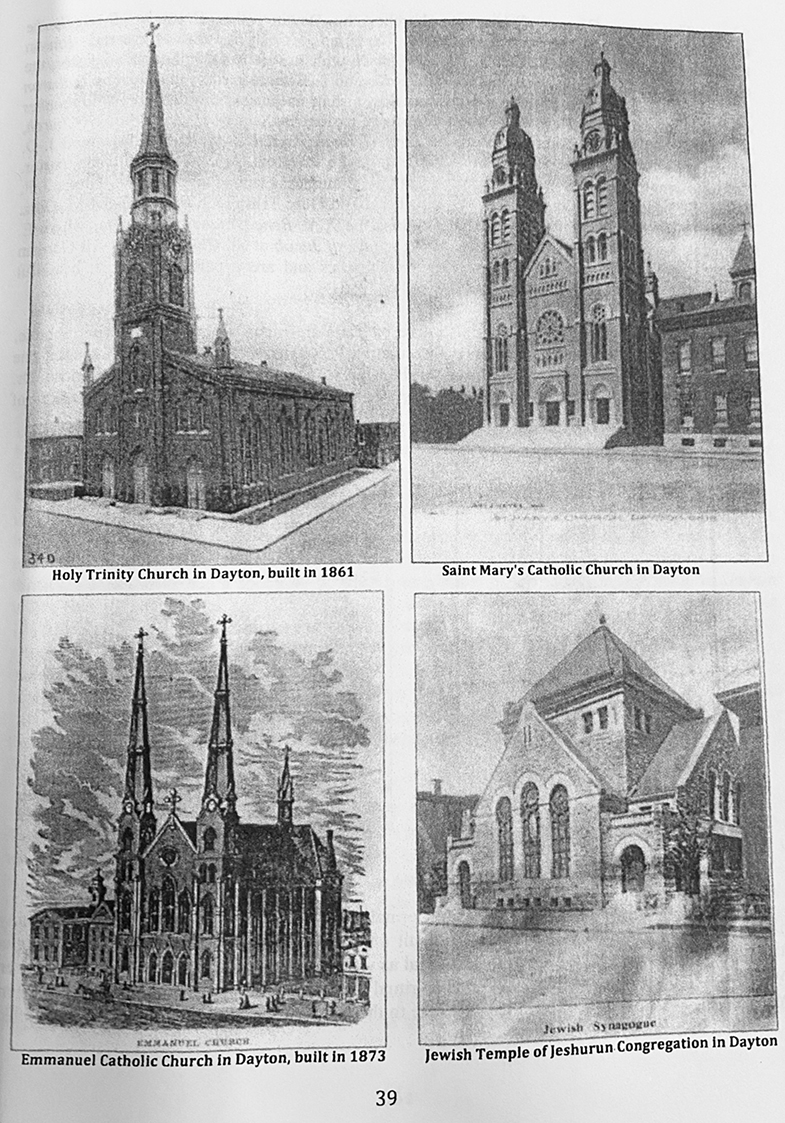

The 1928 book, German Pioneers of Montgomery County, Ohio: Early Pioneer Life in Dayton, Miamisburg, Germantown, based on the lectures of H.A. Rattermann, a scholar of the history of Germans in the United States, includes a photo of B’nai Yeshurun on Jefferson Street (now Temple Israel) on a page along with images of Dayton’s Holy Trinity Church, St. Mary’s Catholic Church, and Emmanuel Catholic Church. Rattermann considered the temple to be among the German houses of worship here.

There was a history of social overlap among Germans in Dayton and Dayton’s Jews from Germany, who settled here mainly between the 1840s and 1870s and had established B’nai Yeshurun downtown. This is where the Israel family worshipped too.

Israel family patriarch Benjamin Israel, born in 1843 in Toren, West Prussia, had fought in the Prussian and Austrian War in 1860 and the Franco-Prussian War in 1870-71. He received medals for valor in both wars. In Dayton, Benjamin Israel was one of the four charter members of the Kriegerverein, a local organization of veterans of those wars.

The Dayton Daily News reported in 1911 that “about 1,000 people enjoyed a genuine old German evening at the Allen School. (B’nai Yeshurun’s) Rabbi David Lefkowitz delivered an interesting address supplemented with stereopticon views of German scenes, and Mrs. Lefkowitz rendered a number of German songs.”

In a 2018 interview with The Observer, a person who used to be responsible for the Liederkranz-Turner archives, which is now at Wright State University, related that one year, when the Nazis were in power in Germany, a member of the Liederkranz chorus held up a small Nazi flag when the group took its portrait on Beth Abraham Synagogue’s steps.

She noted that she had included that photo in the Liederkranz-Turner archival collection when it was given to Wright State in 2013. Despite repeated attempts to locate that image in the collection, The Observer has not been able to find it.

In 1936, an ad in a Dayton Liederkranz concert program featured the endorsement of a Republican candidate for Congress by Father Charles Coughlin of Detroit, whose virulently antisemitic broadcasts reached more than 3.5 million Americans over the radio.

What we know from the papers

The Dayton Daily News (Democratic and owned by James Cox) and The Dayton Journal and The Dayton Herald (Republican and both owned beginning in April 1935 by Frank Knox, owner of the Chicago Daily News) would cover Nazi antisemitism and the Holocaust thoroughly, though the Daily News did so nearly from the beginning of Hitler’s rule in January 1933.

The Daily News relied on Associated Press as its wire service; the Journal Herald often used United Press.

The Daily News distributed a March 28, 1933 AP story about an overflow rally of 57,000 at Madison Square Garden sponsored by the American Jewish Congress to protest the mistreatment of Jews in Germany.

Along with the story, the Daily News published an unsigned editorial taking Hitler to task for raving against Germany’s Jews and for censoring news in Germany, though it still expressed the belief that “now that he has the people in his power, (Hitler) has no real desire to carry out his promises to persecute the Jews.”

A year later, the Daily News and the Herald reported on Germany’s continuing persecution against the Jews.

“Hitler tells the world that ‘the National Socialist revolution is over. It has fulfilled all its hopes.’ When the concentration camps have been emptied, the torturing of dissenters and Jews stopped, Hitler will be believed,” a Sept. 7, 1934 Dayton Daily News editorial stated.

Two months after the Nuremberg Race Laws were enacted against Germany’s Jews, on Nov. 27, 1935, the Herald published United Press’ interview with Hitler in Berlin in which the dictator equated Bolshevism with Judaism.

“The necessity of combatting Bolshevism is one of the fundamental reasons for Jewish legislation in Germany. This legislation is not anti-Jewish but is pro-German. Through these laws, the rights of the Germans shall be protected against destructive Jewish influences.”

The Observer looked at local newspaper coverage at key points in Hitler’s path to his mass extermination of the Jews: the invasion of Austria and the Kristallnacht pogroms in 1938, the invasion of Poland in 1939, the herding of Jews into ghettos in 1940 and 1941, and news of the Final Solution trickling out as early as March 1942.

By Kristallnacht — Nazi Germany’s attacks on Jews, their property, businesses, and synagogues on Nov. 9 and 10, 1938 — the Herald matched the Dayton Daily’s coverage. The papers also ran wire photos of the damage in the aftermath of Kristallnacht.

“World indignation over persecution of Jews in Germany has had the effect of hastening solutions for this aspect of the refugee problem,” read a hopeful Nov. 18, 1938 Dayton Herald editorial.

“Before the closed gates of the world, another persecution appeals,” a Nov. 26, 1938 Dayton Daily editorial lamented. “Nazi Germany lays savage hand upon its fewer than a million Jews. Poland makes life hard for its 3.5 million Jews. Fascist Italy starts persecuting the Jews. Wanted: A land of refuge for 5 or 6 million Jews! There are still vast, empty spaces on the earth. Where is one such to serve as a refuge for the Jews?”

The Herald published that editorial a day after it ran a UP news story that “The British government cannot increase Palestine emigration at present because it might prejudice the forthcoming Jewish-Arab conference, Malcolm MacDonald, colonial and dominions secretary, told parliament…’when we promised to facilitate a national home for Jews in Palestine we never anticipated this fierce persecution in Europe. We made no promise that Palestine should be a home for everyone seeking escape from such a calamity. Palestine’s rather meager soil cannot support more than a fraction of the Jews who wish to escape Europe.'”

Dayton’s Jews organize relief

Three hundred members of Dayton’s Jewish community met July 10, 1933 to launch a campaign for the American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee to feed, clothe, and shelter “the Jews who have been driven by the Hitler edict from their homes in Germany and forced to seek humble abode in the slums of the cities,” The Dayton Daily News reported. The $10,000 raised (equivalent to $231,575 today) would also be used for Jewish emigration from Germany, though the United States remained virtually closed to Jews in Germany and Eastern Europe.

In its coverage of that 1933 campaign, the Dayton Daily essentially reprinted the entire speech given to the gathering by JDC’s chairman, Rabbi Jonah Wise, who detailed the desperate needs of Germany’s Jews.

A year later, the campaign drive was reorganized into the United Jewish Council, an annual campaign, with former Ohio Gov. James Cox — publisher of the Daily News — as a key speaker.

In the summer of 1935, Temple Israel’s Rabbi Louis Witt traveled across Europe to learn about the plight of its Jews.

“The cold, planned persecution of the Jews in Germany is far more sinister than any bloody pogrom that might be instituted,” Witt told those at the opening event of the 1935 United Jewish Council campaign, according to the Daily News.

“The right to live is being denied the Jew, in that their right to earn a livelihood is being taken from them. Deprived of such right to earn their own bread, the Jews are being forced into the lowest forms of degradation possible.”

The rabbi added that German nationalism “honestly believes that it will teach the nations how to get rid of the Jew on the basis of their blood, his race blood.”

The United Jewish Council campaign also provided funds for local and national Jewish organizations. However, at the end of 1936, its board agreed that “every appeal be cut to a minimum in favor of the overseas emergency.”

From then on, 70 percent of the money Dayton’s United Jewish Council collected each year went to relief for Jews in Nazi Europe. By 1943, the annual campaign raised $56,450 — $984,186 in today’s money.

The council also approved Witt’s motion in June 1938 that “where an affidavit is furnished by an individual or individuals necessary for an emigrant or emigrants to immigrate to our community, that it is the responsibility of the Jewish community, provided such affidavit is approved by the Jewish Federation for Social Service and furnished at its insistence.”

Rebecca Erbelding, lead historian of the Americans and the Holocaust exhibit, explained that local organizations such as Dayton’s Jewish Federation were generally not permitted to sponsor individuals or groups directly. It was groups such as the National Council for Jewish Women, Hebrew Immigrant Aid Society, the American Friends Service Committee, and the National Refugee Service that helped connect refugees with willing sponsors.

Then, organizations such as Jewish Federations “assisted with resettlement — with finding jobs, enrolling in school, obtaining retraining, and general ‘Americanization,'” Erbelding said.

Dayton’s United Jewish Council and Jewish Federation — along with regional Jewish organizations and national umbrella organizations for Jewish rescue and relief — attempted to prepare an infrastructure to accept Jewish refugees from Nazi Europe.

In 1939, Dayton’s United Jewish Council and Jewish Federation agreed to accept a refugee family and a refugee child each month, and to provide them with medical and dental care, furnishings, food, light, and rent.

But between 1938 and 1941, Dayton was only able to resettle 70 Jews who had escaped the Nazis. The vast majority of Jews in Nazi-occupied territory had no way out. Few nations would take them in.

According to the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum, between 1938 and 1941, 123,868 Jewish refugees immigrated to the United States. And after July 1941, emigration from Nazi-occupied territory was virtually impossible.

Immigration of Eastern Europeans had been virtually shut down to “undesirables” by the U.S. Congress in 1924. And yearly allocations of U.S. visas from Germany and Austria were locked in at 27,370.

Even so, numerous news accounts in the aftermath of Kristallnacht reported that the United States and England in particular considered expanding the number of immigrants allowed in from Germany and Nazi-controlled Austria. It didn’t happen.

In November 1938, following Kristallnacht, a Gallup poll asked Americans if they approved or disapproved of the Nazi treatment of Jews in Germany. Ninety-four percent disapproved, six percent approved.

When asked, “Should we allow a larger number of Jewish exiles from Germany to come to the United States to live,” 71 percent said no, 21 percent said yes, and 8 percent had no opinion.

Jews who sought to flee the Nazis were thwarted at every turn by the U.S. State Department and its byzantine, ever-changing, ever-tightening obstacles to emigration from Germany and Nazi-occupied lands.

The German American Bund comes to Dayton

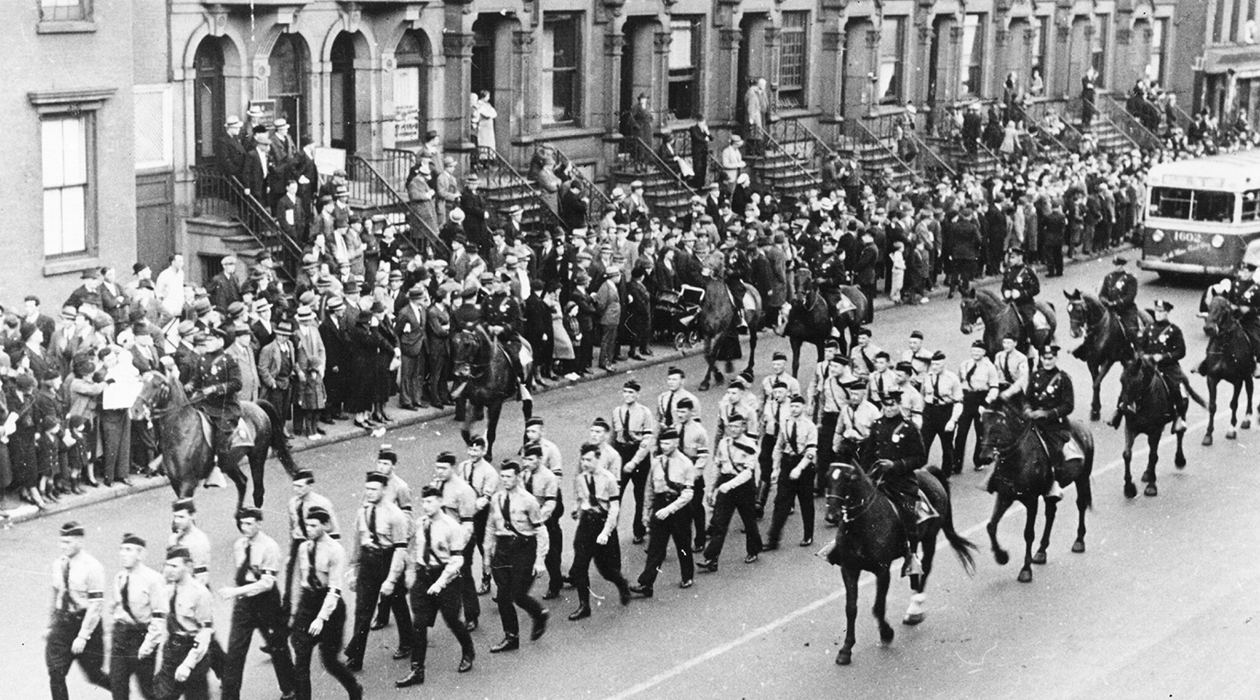

In the 1930s, more than 12 million people of German origin lived in the United States. Of them, the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum estimates that 25,000 became members of the pro-Nazi paramilitary German American Bund after it was established in 1936. The Bund as it was called, was in league with Jew-baiting radio broadcaster Father Charles Coughlin and his Christian Front group.

In Dayton, listeners could tune into Coughlin’s broadcasts on WHIO radio, also owned by James Cox, even as Cox’s Dayton Daily lambasted Coughlin in a Dec. 2, 1938 editorial for telling his listeners after Kristallnacht that the Jews had inspired and financed the Russian Revolution.

A year later, the National Association of Broadcasters established its own self-regulating code committee to force Coughlin off the air.

Officially, Bund members were supposed to be American citizens of German lineage. Most were German citizens. The Bund claimed it had no direct connection to Nazi Germany. It did.

In his book Gangsters Vs Nazis: How Jewish Mobsters Battled Nazis in Wartime America, Michael Benson writes that “the distinction was legal as well as moral. The instant that the Bund admitted to representing a foreign power, it would lose the protections of the U.S. Constitution.”

Daytonians read in their local dailies about violence and riots at Bund meetings across the country, that members of the American Legion would show up and physically attack Bund members.

What Daytonians didn’t know was that Jewish mobsters and their Jewish muscle men disguised as American Legion members would assault Bund members, and that it was at the secret behest of a Jewish judge in New York City.

In mid-February 1938, the Dayton Herald and Dayton Daily News announced that a national Bund leader, G. Wilhelm Kunze, was scheduled to speak in Dayton on March 17 at Liederkranz Hall, and that “plans have been discussed for opening a Nazi camp in this vicinity.”

A day after the report, the Dayton Daily ran an update that Liederkranz society officials had reversed course.

“Members of the Dayton Bund engaged the hall for the speech about four weeks ago, according to Christ Koerner, Liederkranz secretary who booked the meeting. In the light of the widespread antagonism which Kunze’s addresses have aroused, however, Henry Funder, president, and Carl Shultheis, treasurer, conferred with Koerner Tuesday morning and arrived at the decision to cancel the lease of the hall.”

The Herald reported on March 16, 1938 that Kunze would arrive in Dayton the next day as originally scheduled, but that he would only meet with members of the Dayton Bund and its president, William G. Ruhnke, along with a small group of invited guests in a private session.

The update added that “the Dayton Bund has severed connections with the Federation of German Societies, it was learned, in order not to embarrass members of organizations affiliated with the Federation.”

Also prior to and because of Kunze’s visit, the Dayton Daily printed a statement on March 12, 1938 from six local veterans groups expressing their “avowed opposition,” albeit indirectly, to “certain movements which they term ‘un-American.'”

The Dayton Bund held the private meeting on the evening of Thursday, March 17, 1938 at the Gibbons Hotel.

Present were 15 local Bund members, five invited guests including American Legion Post 5 Commander and Steele High School Principal Jay William Holmes, and one reporter each from the Daily News and the Dayton Journal.

In an interview more than two decades ago with The Observer, Maxwell Nathan said the Journal assigned him to cover the meeting at the insistence of the Dayton Bund. It would only allow him, a Jew, to cover the meeting for the Journal, with no explanation given.

Nathan’s March 18, 1938 piece reported that Kunze outlined the Bund’s purposes and delivered an “antisemitic attack” at the meeting, “an attack on an ‘atheist and international movement’ described as threatening the United States.”

The Dayton Daily’s coverage quoted Dayton Bund President Ruhnke as saying the session “was purposely made a closed meeting after conferences with the American Legion’s Holmes.”

Kunze wore a gray shirt with “an emblem in his tie pin.” He opened his address with the Nazi salute, which he explained was also, “in the case of the Bund, the greeting from one Aryan to another.”

As the newspapers reported, American Legion Post Commander Holmes followed Kunze’s talk with his own comments about what patriotism meant to Americans, and that his high school was “made up of all races and creeds, and the finest traits and characteristics were found in no one class or group, but in all of them.”

A week later, Dayton Bund President Ruhnke resigned his post and said he would quit the organization when his membership expired a week later.

Ruhnke told the Dayton Herald that his resignation and withdrawal from the Bund “had nothing to do with an investigation of the organization instituted at Columbus by (state) Attorney General Herbert S. Duffy.”

In response to the accusation that the national Bund had plans for three camps to open in Ohio, including one in Dayton, Ruhnke told the Herald that the report was “the silliest thing ever.”

Carl Shultheis, treasurer of the Dayton Liederkranz society, published a letter April 22, 1938 in the Dayton Daily in his role as president of the Federation of German Societies of Dayton, comprising 20 local German organizations.

“The German American Bund has no connection whatever with any of the German-American societies in Dayton,” he wrote.

“The Federation had nothing whatever to do with the engagement of William Kunze in Dayton recently, and is not interested in or connected with the movement in which Kunze is engaged…it takes no part in the propagation of any foreign doctrine of any kind whatever.”

Journal reporter Maxwell Nathan told The Observer that was the last he ever heard about the Bund in Dayton.

Daytonians would read an AP report in the Nov. 19, 1938 Daily News, 10 days after Kristallnacht, of a speech in Queens, N.Y. by Bund national head Fritz Kuhn, proclaiming that the Bund “is out to do for this country what Hitler is doing for Germany, namely, rid it of the Jews.”

Membership in the Bund across the United States shrank after Kuhn was convicted in 1939 of embezzling Bund funds and was sentenced to prison. On his release in 1943, he was rearrested as an enemy agent and deported to Germany after the war. G. Wilhelm Kunze was indicted for membership in a Nazi spy ring in 1942. He was sentenced to federal prison and released in 1945.

The U.S. government outlawed the Bund in December 1941, when the U.S. entered World War II.

America First’s turn

To Nazi Germany, the German American Bund had become an embarrassment. Germany then encouraged Nazis and Nazi sympathizers in the United States to support the America First Committee, which began in 1940 as an isolationist movement to keep the United States out of the war in Europe.

It started as a movement of college students and grew into a grassroots mobilization of Americans who recalled the horrors that American boys faced in World War I. America First would become infiltrated by Nazis and Nazi supporters.

Instructions from the Nazi government to its America First operatives: stick to the single message of keep America out of the war. America First membership peaked at about 800,000.

Its most famous spokesperson was American aviation hero Charles Lindbergh. His speech in Des Moines, Iowa on Sept. 11, 1941, went “off message” when he said, “The three most important groups who have been pressing this country toward war are the British, the Jewish, and the Roosevelt administration.”

Lindbergh added that he could not condone “the persecution of the Jewish race in Germany,” but that the Jews, “instead of agitating for war, should be opposing it in every way, for they will be among the first to feel its consequences.”

Daytonians read about it in the Daily News and the Herald.

Eight days later, on Sept. 19, 1941, U.S. Sen. Gerald Nye of North Dakota spoke to 2,500 people at Memorial Hall in Dayton as part of a meeting of the local committee of the America First movement.

“Local members of the CIO (Congress of Industrial Organizations) formed an 18-man picket line in front of the hall before and after the meeting,” the Journal Herald reported. “The signs carried anti-Nazi and anti-America First statements.”

The most applause of the evening, lasting for two or three minutes, The Journal Herald reported, was given to the name of Charles Lindbergh.

In an interview with the Journal Herald after the speech, Nye said he approved of Lindbergh’s Des Moines speech a week earlier.

“I agree with Lindbergh that the Jewish people are a large factor in our movement toward war,” Nye said. “This is only natural. The Jewish people have suffered under the Nazi regime and they wish to see the Nazis defeated. For the same reason that the Jewish people in this country are among the leaders of the war movement, the German people in this country are often found in the ranks of those who wish to avoid entanglement.”

In his speech, Nye said that neither Lindbergh nor any other leaders of America First were antisemitic.

“The Nazis have not been working secretly in America for nothing in the decade past,” a Nov. 10, 1941 Dayton Daily editorial stated about America First.

“There is a relatively small but highly vocal element here which wants Hitler to win the war. To that end, they want America to help, not hinder, Hitler’s fight…The sincerely pacific (pacifist) members of America First have found themselves, by their affiliation, helping Hitler. They discover that the leaders with which they find themselves associated in America are heroes in Berlin.”

The Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor on Dec. 7, 1941 and the United States’ entry into World War II marked the dissolution of the America First Committee.

Dayton attorney Irvin G. Bieser, a leader with Dayton’s America First Committee, was quoted in the Dec. 8, 1941 Journal Herald: “The time for argument concerning national policy is passed. Now we must join together and prosecute the cause of the war to its fullest extent.”

The genocide of Europe’s Jews

It was in January 1942 when the Nazis formulated the “Final Solution to the Jewish Question,” the mass murder of all Jews in the lands it held. Confirmation to the outside world came on Aug. 29, 1942 from the World Jewish Congress’ representative in Switzerland, who attempted to telegram the information to World Jewish Congress President Rabbi Stephen Wise in New York.

The U.S. State Department intercepted the telegram, calling it a “war rumor.” Wise received the message from another source, and in November 1942 informed the press in the United States of the Final Solution and that the Nazi regime had already slaughtered more than 2 million Jews in its grasp.

In Dayton, elements of the big picture came through news reports beginning as early as March 16, 1942, when the Dayton Herald carried a UP report from Stockholm, Sweden that “Neutral sources said today that Germans had started a new systematic mass extermination of Jews in western (white) Russia and the Baltic countries and that the victims included many Jews just deported from Germany, Austria, Czechoslovakia and other occupied countries,” including 86,000 Jews in Minsk, tens of thousands in Lithuania and Latvia, and that in Estonia, the entire Jewish population of 4,500 had been killed.

The Herald carried a report on June 26, 1942 distributed from London by its owner, the Chicago Daily News, that “out of the gray horror the Nazis have made of Poland came new evidence today of the systematic extermination of the Jewish population with the death toll from various causes now estimated at more than 700,000.”

“According to a special report sent through secret channels to representatives of the Polish national council here, disease and starvation are allowed to operate to the fullest extent. Where these means are considered insufficient or slow, massacre tactics often are substituted, these sources say. Polish sources insist the Nazis are using portable gas chambers in some sections…one such instance was reported at the village of Chelmno, near Lowicz, where Jews were crowded 90 at a time into the chamber.”

American Jewish organizations appealed to Jews across the world to observe Dec. 2, 1942 as a day of mourning and prayer for the victims of Hitlerism, the Dayton Daily News reported.

“The appeal pointed out that 2 million Jews already had died and that 5 million others are threatened with extermination under a new Hitler order…The organizations pointed out that the ‘greatest calamity in Jewish history’ had occurred and that millions of Jews now ‘live in the shadow of impending doom.'”

By the end of the war in Europe, more than 6 million Jews would be exterminated at the hands of the Nazis and their accomplices.

At Passover 1943, the Dayton Herald’s April 22 editorial read, “In time to come the people of a later generation will read with greater horror than we can now anticipate the bloody record of our age, on which the darkest blot will be the wholesale extermination of the Jews in Nazi-conquered lands. This slaughter has been largely overshadowed by the clash of armies in global war, but it will not be overlooked when the history of our era is recorded. For it was with the massacre of the Jews that Adolf Hitler began his assault on our civilization.”

Marshall Weiss is editor and publisher of The Dayton Jewish Observer and project director of Miami Valley Jewish Genealogy & History.

In conjunction with the Americans and the Holocaust exhibit at the Dayton Metro Library’s main library, Marshall Weiss will present the talk Daytonians and the Holocaust: The View from Here at 7 p.m., Monday, June 5 at the main library, 215 E. Third St. The free program is also presented by Miami Valley Jewish Genealogy & History. Reservations are requested at daytonmetrolibrary.org.

To read the complete June 2023 Dayton Jewish Observer, click here.