A lot of promise

Sacred Speech Series

Jewish Family Education with Candace R. Kwiatek, The Dayton Jewish Observer

Elkanah was disheartened. His second wife, Peninnah, had many sons and daughters, but his beloved first wife, Hannah, was constantly distraught over her childlessness and Peninnah’s merciless taunting.

Every year, the entire household would go to the Tabernacle in Shiloh where Elkanah would worship and offer a sacrifice to God.

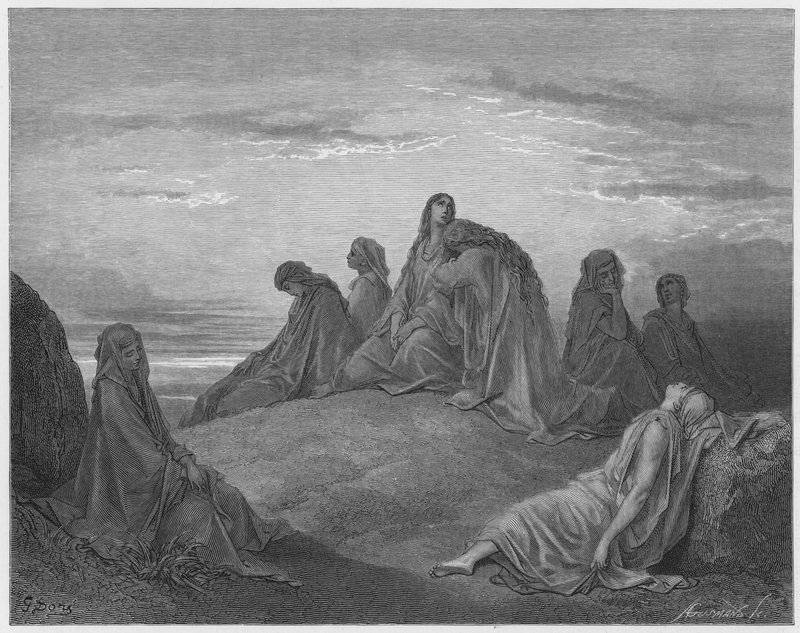

One year, in desperation, Hannah approached the Tabernacle and poured out her heart to God, vowing that if she conceived a son, she would dedicate him to the Lord’s service.

A year later, she gave birth to Samuel. As promised, once he was weaned, Hannah returned with him to Shiloh where Samuel grew up and eventually served God as a prophet, priest, judge, and kingmaker.

“A promise is essentially a commitment…a sworn statement of intention…where one binds oneself to an action, behavior or undertaking,” the self-improvement blog site Craft of Man explains.

Fundamental to the rise of ancient civilizations, promises were viewed as sacred obligations, not merely social contracts.

They maintained social order by establishing moral expectations and consequences, thus assuring truthfulness and accountability in legal, political, and judicial arenas, and fostering trust between individuals, among communities, and in foreign relations.

Promises are “pillars of society,” the blog site concludes.

In the modern world, it’s impossible to go through a single day without directly or indirectly encountering some form of promise.

The maxim “promises made, promises kept” emphasizes the importance of fulfilling such commitments.

At the same time, according to Rabbi Berel Wein, “in most legal systems in the world, agreements that are not committed to writing and then signed by the parties are of little enforceable value.”

However, Judaism retained the ancient view that a promise is a binding verbal commitment, a moral obligation, whether or not recorded in writing.

An early biblical archetype of this notion is found in God’s spoken promises to Abraham. He would become a great nation of countless descendants and material success, both blessed and a blessing to others, with a name of wide renown and an inheritance in the land of Canaan.

These spoken promises are still in effect. This Jewish mindset, conveyed by the modern aphorism “Saying is signing — it is committing and it is binding,” is evident even today in New York City’s traditional Jewish community, most notably within the Diamond District, where business deals are regularly finalized with only a verbal agreement and a handshake.

In Judaism, promises have always been a serious undertaking.

A covenant (brit) is a long-term relational promise between God and humankind, typically involving moral or spiritual commitments. The most central to Judaism is arguably the Covenant at Sinai, when God gave — and Israel accepted — the Torah.

Filled with moral and ethical laws, stories, and wisdom to guide Israel’s relationship with the Divine and with one other, this covenant established Israel as God’s chosen people.

A vow (neder) is a solemn, sometimes conditional, promise made to God about performing a specific action or refraining from doing something permitted, effectively creating a new personal law.

The first to utter a vow in the Torah was Jacob who, on the run from Esau, vowed that if he were protected, provided for, and returned home safely, the Lord would be his God to whom he would dedicate a tenth of everything.

An oath (shevuah) is a sacred declaration or promise about one’s actions — “I swear I did (or won’t do) such-and-such.”

It can also express a commitment to fulfill an obligation — “I swear to uphold the law.”

In the Book of Joshua, Rahab rescued the two Israelite spies in Jericho. In return, she requested they swear an oath to spare her and her family during the conquest of the city, a promise they willingly fulfilled.

The Torah itself explicitly commands keeping one’s word. “If a householder makes a vow to God or takes an oath imposing an obligation on himself, he shall not break his pledge; he must carry out all that has crossed his lips.”

By the rabbinic period, however, oath-taking was limited and the practice of making vows had fallen out of favor.

In the Talmud, where the majority opinion was to refrain from vows altogether, those who fulfilled their vows were called wicked and sinners.

The story of Jephthah’s vow may offer a clue why. In a desperate plea for victory against the Ammonites, Jephthah vowed to sacrifice the first thing to come out of his house to meet him upon his victorious return. Tragically, his only daughter was the first to greet him, but Jephthah nonetheless fulfilled his vow.

To solve the problem of vows and oaths made in haste, in a state of anger, without considering the implications, broken or left unfulfilled, inadvertently violated or forgotten altogether, the Talmudic rabbis developed an elaborate court procedure for their annulment.

They also invented Kol Nidre, a ritual declaration rendering invalid all unintentional vows and oaths of the past and upcoming year.

And to avoid making an accidental vow, the modern expression bli neder (without a vow) came to be recited alongside a promise or commitment to indicate it’s not intended to be binding like a vow.

Hershele’s promise: serious undertaking, sacred obligation, or social contract?

Having run out of money, Hershele borrowed a carriage-maker’s whip, cracking it loudly in the street. “Half-fare to Letitshev, today only!”

Hershele soon had a cluster of eager customers. “Where are your horses?” one man asked.

“Follow me,” Hershele replied. “Don’t worry. I’ll take you right to Letitshev.”

They followed him, leaving their town behind. But there still were no horses.

“Don’t worry,” Hershele repeated. “I’ll take you right to Letitshev.” And he did — on foot.

“You swindler!” his customers yelled.

“Didn’t I promise to take you right to Letitshev?” Hershele countered.

“Yes, but in a horse and carriage, not on foot!” they replied.

“Did I ever say anything about horses or a carriage?”

They stood there, dumbfounded, as Hershele hurried away.

Literature to share

Gursha by Beejhy Barhany and Elisa Ung. Gursha is more than just a cookbook: it’s also a memoir of the Ethiopian experience, leaving one’s native land for Harlem. It’s a travel journal through food. It’s the story of becoming a chef and building a restaurant business. It’s an introduction to a unique and fascinating culture and its rich culinary history. And it’s a feast for the eyes! The author is engaging, and the recipes are designed to delight.

Sharing Shalom by Danielle Sharkan and Selina Alko. Based on a real incident, this multiple award-winning children’s picture book tackles the difficult topic of antisemitism through the story of a little girl’s vandalized synagogue. The understated, age-appropriate text captures the youngster’s love of Judaism and her thoughts and emotions about the shocking event. Vibrant illustrations offer an uplifting balance, mirroring the book’s messages of hope, respecting others, and pursuing peace.

To read the complete August 2025 Dayton Jewish Observer, click here.