Maledictions and mosquitoes

Sacred Speech Series

Jewish Family Education with Candace R. Kwiatek, The Dayton Jewish Observer

In the region of ancient Babylonia, the first Gulf War and subsequent looting of Iraq’s National Museum in 2003 resulted in thousands of stolen “incantation bowls” entering international trade markets, according to Israel Antiquities Authority official Amir Ganor.

Twenty years later, as the IAA seized hundreds of illicitly acquired antiquities from a Jerusalem property, they discovered three 1,500-year-old earthenware incantation bowls, also known as “magic bowls” in Jewish circles.

Their geographic and cultural origins were immediately apparent from the distinctive epigraphs written in Jewish Aramaic, the unique language of the Babylonian Talmud.

Spiraling inside the bowls from rim to center, inscriptions included a writ of divorce from a house-invading demon, a quote from Psalms, and the image of a bound female demon labeled, “My brother, the son of Pearl,” Smithsonian magazine author Dieynaba Young reported.

“More than 3,000 bowls like these have been discovered to date,” Newsweek reporter Aristos Georgiou wrote, “the majority of which were created by Jewish people.”

Used primarily as protective amulets, these bowls feature biblical quotations, Mishnaic texts, blessings, Aramaic incantations and spells, references to angels, demon images, magical symbols, and even rabbinic legal formulas, all with the purpose of invoking divine help or warding off curses and other misfortunes.

“May an evil decree come upon him.” “Let him suffer and remember.” “May he find no rest even in the grave.”

“A curse is a verbal invocation pronounced to bring harm, evil, or detriment to another,” Rabbi Geoffrey Dennis explains. “More than a threat or a wish, a curse is assumed to have the power to make the desired harm a reality.”

According to the Talmud, the act of cursing has power regardless of the speaker’s rationale, their level of authority or skills, or their intention — even when it’s uttered unintentionally.

“May his name and his memory be blotted out!”

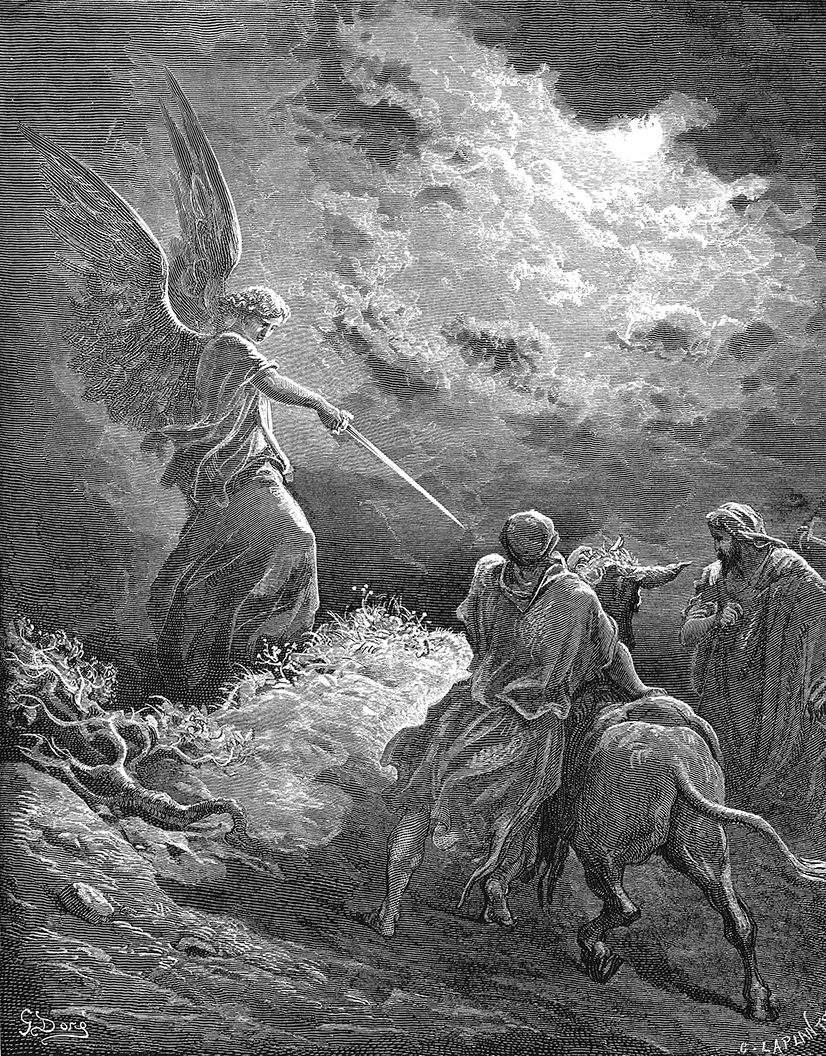

Among the most well-known biblical stories of curses are God’s transformation of the serpent in the Garden into a belly-crawling, dust-eating reptile after enticing Eve to disobey God, the failure of the foreign prophet Balaam to curse the Israelites on behalf of King Balak, and the divine promise that Amalek’s descendants will be annihilated and his memory erased for his unprovoked attack on the wilderness Israelites.

“In the Torah there are more curses than blessings.”

But it is the annual reading of Deuteronomy’s 98 curses, the ones Moses commanded to be recited upon entering the Promised Land, that elicits hints of their otherworldly energy and potent nature.

Belief in — or at least wariness about — the unusual power of curses, deliberate or unintended, has led to the modern custom of rapid, whispered reading of these verses.

“His intestines should be pulled out of his stomach and wrapped around his neck!”

The rabbis of the Talmud initially elaborated upon the biblical attitudes toward curses, continued to stress their efficacy, and even occasionally demonstrated their own power to curse.

Over the centuries, however, limitations on the use of curses were significantly expanded, and eventually curses were permissible only toward those guilty of disgraceful or sinful religious behavior.

Rav Yehuda wisely captured the sentiment of the times by recording a popular adage: “Be the one who is cursed and not the one who curses, as a curse eventually returns to the one who curses.”

“May you have a hundred houses, a hundred rooms in each house, 20 beds in each room, and may fever and chills toss you from one bed to the next!”

Today, Judaism continues to acknowledge the power of curses, although they’re no longer in the form of incantations or magic bowls.

Yiddish, the language of Eastern European Jews, has a vast treasury, in fact a whole genre, of formulaic curses called klole, journalist S.I. Rosenbaum reports.

While many have been passed along as jokes — “May he swallow an umbrella and may it open in his belly!” —others, at the very least, give one pause for thought.

“May all your teeth fall out except one, to give you a toothache!”

“May he have a big store full of goods: May people not ask for what he has, and may he not have what they ask for.”

Rosenbaum continues, “Other Jewish languages also offer choice curses, including Ladino — ‘Who knows if you will finish a year?’— and Judeo-Arabic — ‘May your eyeball burst.’”

But while this long-standing tradition of curses highlights Judaism’s recognition of the tremendous power of words, how does it comport with the Jewish worldview that speech is sacred?

Today’s cursing is not about incantations or magic, but rather profanity, swearing, insulting, and general irreverence.

Furthermore, unlike ancient curses that were targeted and infrequent, today’s cursing is widespread and constant.

This endless barrage is “a powerful force that shapes the way we think, perceive, and understand the world around us,” notes psychologist Mark Travers, a spiritual pollution that plays a pivotal role in forming our attitudes and beliefs.

Such indiscriminate cursing also arouses baseless hatred, ultimately bringing about great evil upon individuals, communities, and the world.

Rabbi Mordechai Becher concludes, “Although ‘curse words’ may be common, so are mosquitoes! (One) should avoid both. Speech should reflect the best of who we are and what type of person we want to become.”

After all, “If all curses actually materialized, the world would be done for.”

Literature to share

Red Sea Spies by Raffi Berg. Most Jews have heard of Operation Solomon, the 1991 covert Israeli military operation that airlifted more than 14,000 Ethiopian Jews to Israel in two days. Less well known is Operation Brothers, an earlier clandestine mission (1979-1984) involving a Mossad-run luxury diving resort on the Sudanese coast and Israeli Navy Seals who ultimately smuggled about 8,000 people to Israel. This meticulously researched nonfiction thriller is the real story, gripping the reader in the first few sentences and never letting go.

Ping-Pong Shabbat: The True Story of Champion Ester Ackerman by Ann D. Koffsky. At 7, Estee began playing Ping-Pong in her family basement. She was soon competing in tournaments. At 11, she made the finals of the U.S. National Table Tennis Championships. Winning the final match would give her the gold. But it was scheduled on the Sabbath. How could she, a Modern Orthodox Jewish girl, pursue her passion and still honor Shabbat? Dynamic illustrations enhance this engaging biography for elementary grades. A perfect family or classroom discussion starter about values.

To read the complete May 2025 Dayton Jewish Observer, click here.