Survivors who wrestled with their conversions to Christianity form basis of UD assistant professor’s first book

By Marshall Weiss, The Dayton Jewish Observer

University of Dayton Religious Studies Assistant Prof. Abraham Rubin’s first book release brought him to New York for a Feb. 3 lecture at the Center for Jewish History sponsored by the Leo Baeck Institute for the Study of German-Jewish History and Culture.

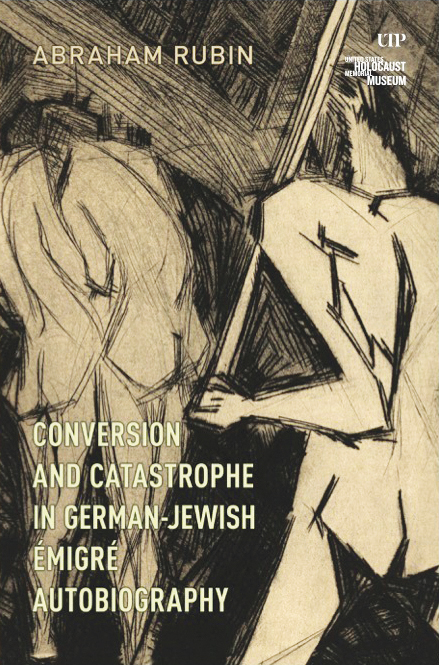

In Conversion and Catastrophe in German-Jewish Émigré Autobiography, published by University of Toronto Press in association with the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, Rubin profiles four German Jewish Holocaust survivors — all men of letters — who converted to Christianity after they were out of harm’s way.

For the rest of their lives, however, they felt compelled to recount and justify how and why they became Christians.

“They were out of reach of the Nazis, and they still decided to convert,” Rubin says. “The question is why they decided to do it, and how they tried to frame that story to multiple audiences, because they knew this was a very controversial move to make in the wake of the Shoah, where you’re considered a traitor to your people.”

Rubin, who arrived at the University of Dayton in 2022, says his book digs into their published and unpublished conversion narratives.

“A lot of the times, they say, ‘Well, this conversion has allowed me to become a better Jew,’ which is a very familiar story to Christianity. That’s essentially the basic narrative of Christianity. It’s called supersessionism or replacement theology: that the Mosaic revelation has been surpassed with the coming of Jesus.”

He says their conversions were a way to distance themselves from their stigmatized, persecuted identities as Jews.

“You think of these people as standing outside the fold of Jewish history,” Rubin says. “What do they have to do with us? They no longer identify as Jews. And the answer is, they have a very intense and ongoing dialogue with other paths that Jews in the modern era have taken. And part of their own attempt to justify their own religious choices is by debunking other alternatives.

“One of the things that comes up again and again in all of these stories is the vilification of other Jews. Sometimes there are these very shocking passages.”

One figure Rubin profiles, Karl Jakob Hirsch — a great-grandson of Rabbi Samson Raphael Hirsch of Frankfurt —wrote in 1946 that the Holocaust was a punishment, the Jews’ path from the crucifixion of Jesus in Golgotha to Auschwitz.

Rubin says Hirsch’s message was well-received when it was published in immediate post-war West Germany.

“It’s kind of a theological gloss on the Shoah that appeals to the German audiences.”

Hirsch and the other three, Rubin says, thought they might find common ground with their former German audiences, at least by embracing their faith. They didn’t succeed.

In their post-conversion writings, all were critical of their parents’ liberal Judaism, the Judaism common in Germany in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, Rubin adds.

“Many times, they present their own embrace of the Christian faith as a more authentic Jewishness than their parents’.”

Rubin, who was raised in Haifa, Israel, specializes in German Jewish thought.

“German Jews in the 20th century are constantly trying to make sense of, how do we define our Jewishness, how do we understand ourselves as Jews, as Germans? I was just fascinated by how this drama unfolds and continues after 1933, even in cases where Jews are no longer self-identified as Jews. Some of these very central questions of German Jewry continue to unfold in the German Jewish diaspora.”

UD’s Spearin Chair in Catholic Theology will host a book release program/reception for Abraham Rubin’s new book, 5-6:30 p.m., Monday, April 7 at the Roger Glass Art Gallery, 29 Creative Way, Dayton. Rubin will talk about the book in a conversation with Beth Abraham Synagogue Rabbi Aubrey Glazer.

To read the complete March 2025 Dayton Jewish Observer, click here.