Survivor, retired Central State professor, philanthropist dies at 93

By Marshall Weiss, The Dayton Jewish Observer

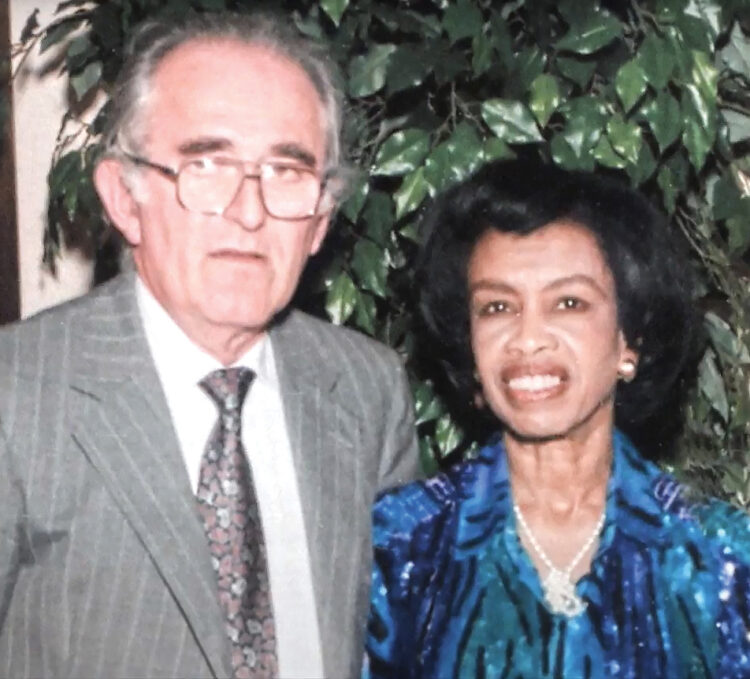

Aleksandar Svager, who along with his wife, the late Thyrsa Svager, funded numerous college scholarships for African American women to complete their degrees in mathematics, died Oct. 3 at Brookdale Oakwood. He was 93.

“He always thought about helping people in my sister’s culture because education was quite important to the man,” Thyrsa Svager’s sister, Constance Robinson, told The Observer. “He was always about educating people in math and science. He really wanted people to excel.”

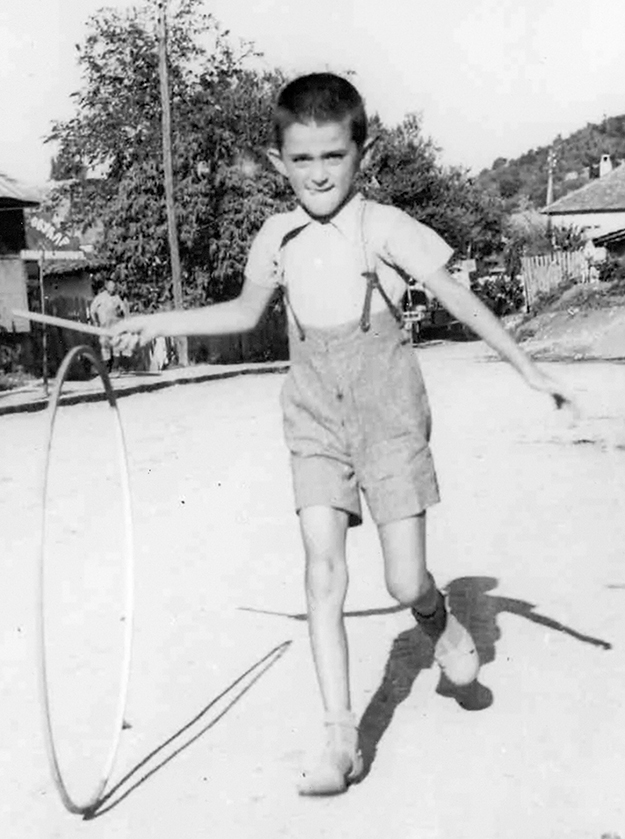

At age 10 in 1941, Svager and his parents fled their home in Sarajevo, Yugoslavia hours before the Nazis were to arrest and transport them to Auschwitz, Robinson said.

“They got as far as Italy before they were taken to a prison camp. I’m not sure which one it was.”

Robinson said her late brother-in-law rarely talked about his story of survival when he married into her family. To her knowledge, he never wrote about his Holocaust experiences or recorded them for an oral history.

She shared as much as she knew.

“When they were escaping, he didn’t talk for about three months. When they got to the prison camp, he didn’t talk. Because he was told to be quiet.”

Svager managed to roam the streets around the prison camp in Italy and became a money changer for the shopkeepers in the surrounding town.

He obtained food to sustain his family on the black market and from sympathetic townspeople.

“And the shopkeepers liked him because they didn’t think that the police would come after him since he was a boy,” Robinson said. “It was bad, but it could have been much worse.”

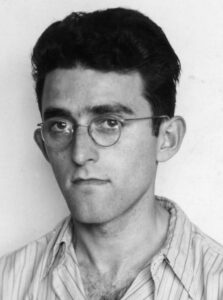

When World War II ended, the Svager family returned to Yugoslavia. Aleksandar Svager studied and taught at the Nuclear Institute of Zagreb and the University of Sarajevo.

He obtained a student visa in 1960 to study in the United States and left the Communist country for Texas Christian University in Fort Worth, where he earned his master’s degree in physics.

“After that, he got a master’s of art so he could get a teaching job and prolong his educational stint without putting his relatives (in Yugoslavia) in danger,” Robinson said.

He arrived at Central State University — the public historically Black land-grant university in Wilberforce — in 1964 as a professor of physics. Within a year, he chaired CSU’s first Computer Science Department.

It was at CSU where he met his future wife, Prof. of Mathematics Thyrsa Frazier. According to the American Physics Society, she was the 10th African American woman to receive a Ph.D. in math.

On CSU’s commencement day in 1968, they were married at her parents’ home in Wilberforce.

Although interracial marriage had been legal in Ohio since 1887 — when the state’s “anti-miscegenation” law of 1861 was repealed — it didn’t become legal across the United States until June 12, 1967, when the Supreme Court ruled in favor of Mildred and Richard Loving in Loving v. Virginia.

“They were a good match for each other,” Robinson said of Thyrsa and Aleksandar Svager.

“Since Wilberforce is predominantly African American, they were much more accepting of my brother-in-law, and since he was on the faculty and chairperson of the physics department, and she was the chairperson of the mathematics department, it was a lot better than it could have been.”

The Svagers decided they wanted to help female African American students pursue and obtain mathematics degrees.

The couple lived on one paycheck. They saved the other to fund scholarships.

“They never had children,” Robinson said. For three decades, they helped students they knew who were in need.

“Whenever a kid needed money, we gave it and we never said it was a gift or a loan,” Aleksandar Svager told the Springfield News-Sun in a 2017 interview.

Thyrsa Svager retired from CSU as provost and vice president for academic affairs in 1993. Aleksandar Svager retired in 1996.

After his wife’s death in 1999, he established the Thyrsa Frazier Svager Scholarship Fund through The Dayton Foundation’s African American Community Fund. To date, the fund has awarded scholarships totaling $101,000 to 28 students.

“I wanted a way to remember my wife,” he told the Springfield News-Sun. “Since she and I had always helped students, I needed to create a scholarship fund.”

Robinson said Aleksandar Svager wasn’t religious until after his wife died. “They did have a menorah in their window, but he also gave each of the nieces and nephews (his wife’s family) a crisp $100 bill for Christmas, even after they graduated from college. He was generous.”

Temple Israel Rabbi Emeritus David Sofian met Svager in 2004 when he came to the Dayton congregation to talk about burying his mother.

“I distinctly remember merely asking him to tell me about her,” Sofian said. “His answer was long and detailed, giving me everything I needed to proceed with the funeral. He used to tell me I got him to talk more about himself and his family that day than anyone else ever had. We became friendly after that.”

The rabbi said Svager joined the temple and attended its Torah study class almost every Shabbat morning, “contributing interesting comments, mostly stemming from his background, which everyone in the group enjoyed.”

Sofian said Svager was often the first one to arrive for Torah study. “He liked to laugh, and I was happy to see him each Shabbat morning. Indeed, he was such a regular, if he wasn’t there, we worried that maybe something happened.”

Svager was the lead donor when the temple commissioned a new Torah scroll in 2007.

It was at about that time when Svager began sharing his story with students and community groups in Xenia.

He lit one of the six memorial candles at the 2018 Greater Dayton Yom Hashoah Observance, held at Beth Jacob Congregation.

One middle school student who heard his testimony at school wrote,” Dr. Svager’s story is one that I’ll remember for the rest of my life.”

To read the complete November 2024 Dayton Jewish Observer, click here.