Sticks and stones

Sacred Speech Series

Jewish Family Education with Candace R. Kwiatek, The Dayton Jewish Observer

The Talmud tells of a man who prepared a party, but the invitation to his friend Kamtza mistakenly went to his sworn enemy, Bar Kamtza. When the host discovered his enemy at the party, he ordered, “Get out!” Bar Kamtza offered to pay for his food, or half the cost of the party, even for the entire party to stay and avoid public embarrassment.

But the host threw him out as the sages and guests watched, silent. Humiliated and disillusioned, Bar Kamtza went to the Roman emperor and maliciously reported, “The Jews are rebelling against you.” The emperor asked for proof. “Send them an offering,” said Bar Kamtza, “and see whether they will offer it on the altar.” So the emperor sent him back with a calf on which Bar Kamtza made a blemish, making it ritually unacceptable for sacrifice.

In order not to offend the emperor, the rabbis were inclined to offer it, but Rabbi Zechariah pointed out it would set an unholy precedent. So the sacrifice was not offered. As a result, the emperor appointed Vespasian to suppress the Jewish revolt. He reestablished Roman control over Judea and then besieged Jerusalem for three years before it fell in 70 C.E.

This tale upends the old playground rhyme, “Sticks and stones will break my bones, but words can never hurt me.” In Jewish thought, language used improperly has the power to embarrass, endanger, destroy, and even kill.

Colloquially, all such language, true or not, is referred to as lashon hora, evil speech. One of its most ubiquitous forms is gossip (rechilut), described by Maimonides as “going around telling people what other people have said or done.”

It is unambiguously prohibited in Leviticus: “Do not go up and down as a talebearer (rachil) among your people.”

There are no exclusions either, Jewish author Tracey Rich clarifies: talebearing is prohibited “even if it is not negative, even if it is not secret, even if it hurts no one, even if the person himself would tell the same thing if asked!”

The term for a gossip, rachil, comes from the word rocheyl — a peddler, trader, or merchant. Thus, in the words of Rabbi Jack Abromowitz, “the gossip is like a salesman, going door to door hawking their merchandise…,” dealing in information instead of goods.

While it may appear to be innocuous, gossip often has unforeseeable negative repercussions. Illustrating its pitfalls is a famous Jewish folktale about a town gossip. When he sees the unintended unrest his gossip has caused, he goes to the rabbi for advice on how to make amends. “Go home, cut open a feather pillow, and shake it vigorously out the window,” the rabbi tells him.

When the man returns to ask what to do next, the rabbi orders him to collect all the feathers, every single one, and stuff them back into the pillow. The man stares at the rabbi in disbelief. “That’s impossible! I’ll be lucky to find any — they’ve flown everywhere!” “Just like the feathers,” the rabbi points out, “words once spoken cannot be retrieved.”

There are two particularly egregious forms of talebearing: lashon hora and motzi shem ra. The precise meaning of lashon hora is negative talk about a person, often true and frequently expressed as insinuation or allegation, in a deliberate attempt to cause harm.

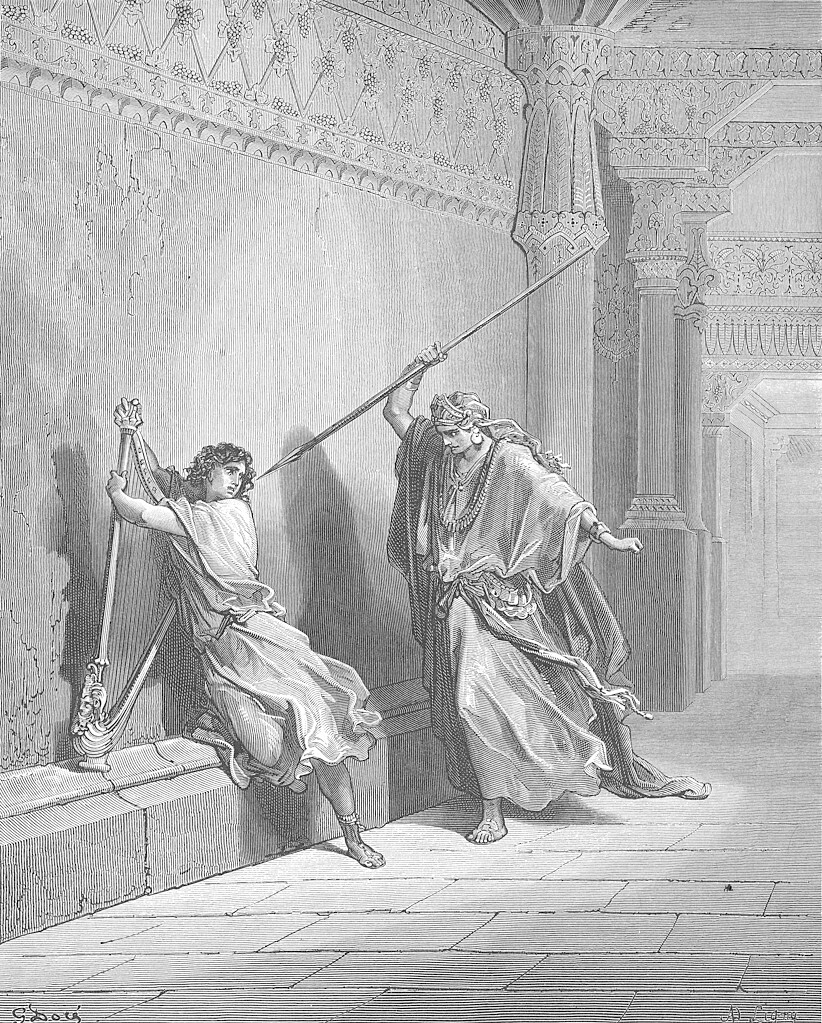

A biblical story about Saul’s jealousy of David provides a classic example. Despite David’s sworn allegiance, King Saul set out to kill him, so David fled to the priestly city of Nob. Having observed the events there, the evil royal herdsman Doeg the Edomite accurately reported to Saul that the priest gave David provisions and a weapon, but implied that all the priests were conspirators with David and had armed him to kill the king. Saul ordered Doeg to kill them all. Doeg eagerly killed the 85 priests along with their wives, children, and nursing babies.

Religious educator Jay Gallimore concludes, “Such were the results of ‘truth’ cooked into gossip for personal gain and fed to an appetite that craved it.”

Motzi shem ra, bringing about a bad name, involves spreading malicious or damaging lies, hearsay, rumor, or false reports about another person in speech (slander) or writing and imagery (libel).

Collectively known as defamation or calumny, it is considered in Judaism to be the worst type of speech. Unfortunately, we can observe motzi shem ra reaching epidemic proportions in the social environment and media today. One particularly egregious example is the modern iteration of the age-old blood libel against the Jews.

“In recent years, there have been a number of antisemitic accusations of Israel harvesting organs of Palestinians,” reports the ADL. Since the Oct. 7 massacre in Israel, anti-Israel voices from America, Europe, and Australia have increased the volume of cartoons and social media posts that accuse Israel of stealing organs from Palestinians killed in Gaza, claim that murder of children is a preferred Israeli ritual, assert that Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu drinks Palestinian blood, and recall the ancient libel in images of bleeding babies.

Judaism is intensely aware of the wondrous power of speech as well as its potential for harm. We read in the Torah that the entire universe was created with words.

In the name of Rabbi Yosei ben Zimra, Rabbi Yohanan teaches that the tongue is an instrument so dangerous it must be kept hidden from view and behind two protective walls (teeth and lips) to prevent its misuse.

Of the 43 sins enumerated in the confessional Al Chet prayer recited on Yom Kippur, 11 have to do with speech. According to the prophet Jeremiah, speech is like an arrow: once words are released, they cannot be recalled, the harm they do cannot be stopped, and the harm they do cannot always be predicted, for words like arrows often go astray.

We are obligated to respect every person as created in the image of God, especially in our speech. And the Talmud warns that speech about a third party has the potential to kill three: the one who speaks, the one who listens, and the one about whom they speak. We ought to keep these in mind every time we open our mouths to speak.

Literature to share

The Madwoman in the Rabbi’s Attic: Rereading the Women of the Talmud by Gila Fine. Among the mostly marginal and anonymous women of the Talmud are six exceptions who, at first glance, appear to be a feminist’s nightmare. But all is not as it seems on the surface. A lecturer of rabbinic literature at Pardes, author Gila Fine does a deep dive into these heroines’ stories in the Talmud and reveals unexpected richness in their characters, in rabbinic views of women, and in moral teachings about how we view the people in our lives.

A Feather, A Pebble, a Shell by Miri Leshem-Pelly. Through inviting watercolor images and lyrical text, the wondrously diverse land, nature, and history of Israel come to life in this unique picture book for primary grades. From the northern forests to the southern desert, a young explorer climbs through caves and canyons, hikes up and down hills, and splashes in rivers and seas. Along the way, she discovers small objects to hold that bring history, the Bible, and more to life, and then leaves the treasures in their habitats for the next explorer to find.

To read the complete November 2024 Dayton Jewish Observer, click here.