What became of Queen Vashti?

By Laura Paull, j. The Jewish News of Northern California

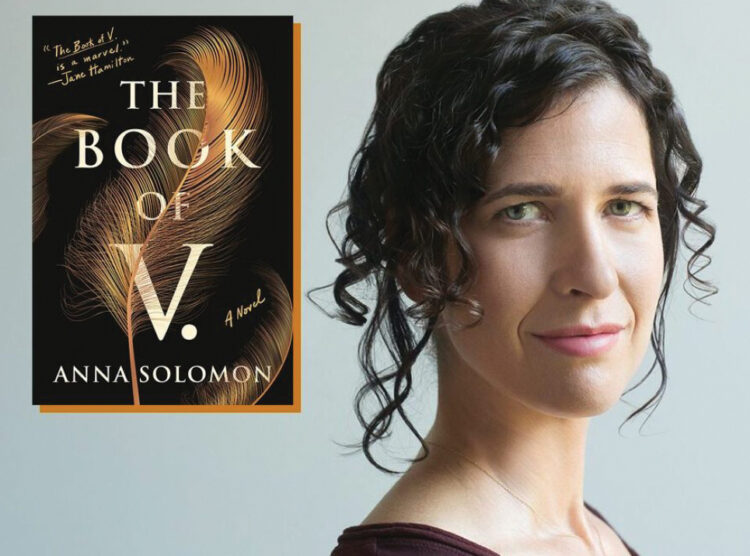

Anna Solomon’s third novel, The Book of V., follows several women in different time periods whose lives offer interpretive windows into the biblical stories of Esther and Vashti.

One character is Lily Rubenstein, a young wife and mother in contemporary Brooklyn, who struggles internally with her chosen status as a stay-at-home parent and as her husband’s second wife.

Their two daughters’ repeated requests for her to read aloud a picture book about Esther, and the need to make their costumes for a Purim celebration, kick off the novel’s central inquiry in Chapter 1: How are we to understand the complicated story of Esther today? And how are women’s lives like, or unlike, that of the Jewish teenager who became a queen against her will?

Another character, the young wife of an ambitious, young U.S. senator in the early 1970s, wonders if she really chose her own marriage. Vivian (“Vee”) Barr was born into WASP privilege, making her selection of a mate obvious and automatic. But Vee’s identity in relation to her husband is thrown into question when he asks her to do something in the interests of his career that is every bit as outrageous as King Ahashverus’ demand of Vashti.

Additionally, Vee’s civic complacency is disturbed when a cross is burned on the lawn of her best friend, who has married a Jew. With the burgeoning women’s movement swirling around her, Vee wades deep into a process of self-definition that asks, radically, what she needs to feel whole, and whether she can stand on her own.

The narratives of Lily and Vee are interspersed with an imaginative interpretation of the story of Vashti and Esther, anchoring the novel.

The narratives of Lily and Vee are interspersed with an imaginative interpretation of the story of Vashti and Esther, anchoring the novel.

Esther’s predecessor, Queen Vashti, is shrouded in mystery. “I don’t know what happened to Vashti. The book doesn’t say. Nobody knows,” Lily explains lamely to her little daughters in the contemporary segment.

But when Solomon recreates the ancient world at the height of Persian power — when Esther’s people were a hardscrabble, migratory lot, and when Esther finds herself sequestered in the royal palace — it becomes pretty clear what happens to women who disobey.

Esther’s extraordinary efforts to warn her Jewish tribe about their imminent destruction is heartrending because she wins back her stolen integrity at the cost of self-sacrifice.

The book “gives voice to generations of women bookending at least 2½ millennia,” said Noa Albaum, program coordinator for San Franicsco’s Jewish Community Library. “These voices call attention to, and speak out against, societal structures of power, domination, and oppression. The characters who hope for and champion the desire for partnership-based societies, despite the obstacles they face, provide hope and inspiration for Lily and for the reader. And they remind us that as far as we’ve come, we still have a lot of work to do.”

The Book of V. brings a fresh eye to the Book of Esther. In a piece in Tablet, the author noted that “what seems a clear-cut tale of good and evil is not so clear when you look a little closer…All the categories that seemed so fixed when I was a kid turn out to be far more fluid, as most of us — if we’re honest — know them in fact to be.”

Solomon pays particular attention to the enigmatic figure of Vashti, who was banished — possibly killed — by Ahashverus after she refused to appear without clothes before the king and his drunken companions. Commentators have long sought to fill in the details, and Solomon offers her own complex and sympathetic take on this and the intertwining of Vashti and Esther’s experiences.

The JCC Cultural Arts & Book Series partnering with Hadassah presents Anna Solomon via Zoom, 6 p.m., Monday, March 1. Free. Click here to register.

To read the complete March 2021 Dayton Jewish Observer, click here.