From eicha to ayeka

The Bible: Wisdom Literature

Jewish Family Education with Candace R. Kwiatek, The Dayton Jewish Observer

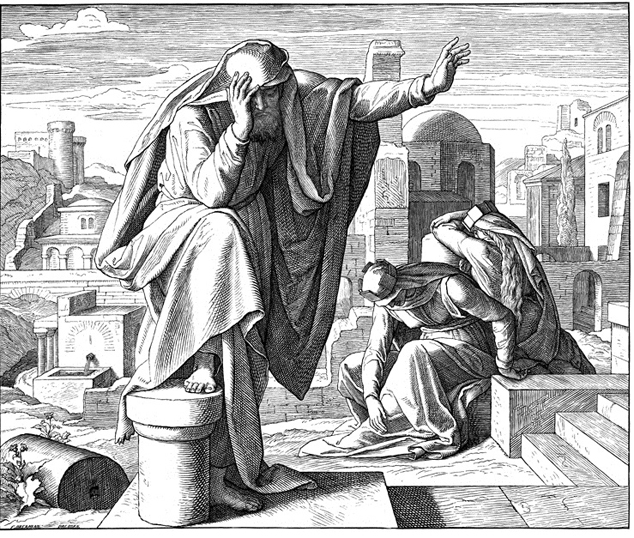

“Eicha — Oh, how has the city that was once so populous remained lonely?” grieves the author of Lamentations. “All her friends have betrayed her; they have become her enemies.”

Eicha’s haunting trope expresses the despair and desolation wrought by the destruction of Jerusalem’s Holy Temples.

According to Jewish tradition, the First Temple was lost because of idol worship, sexual immorality, and bloodshed.

The Second Temple, however, was destroyed because of sinat chinam (baseless hatred) permeating Jewish society, even though the people were otherwise engaged in good deeds.

This teaches that sinat chinam alone is equivalent to the combined evil of the three earlier transgressions.

As baseless hatred is yet again fostering alienation and heartache, splintering the Jewish community and American life altogether, Eicha deserves another look.

Sinat chinam appears in many guises. Incivility. Speaking ill of others. Name-calling. Harassment and bullying. Censorship. Ignoring and shunning. Boycotting. Expressions of scorn, hostility, and loathing. Demonization. False criminal accusations and outright attacks.

“We encounter overt or nuanced forms of hate in the street, in the workplace, and in politics,” notes Rabba Dina Brawer. “That hate is even extended to complete strangers, those we fear will impede our agendas or whose opinions we abhor.”

Neither monstrous people nor psychopaths perpetrate sinat chinam. Like blogger Rabbi Ruth Adar, I have heard otherwise good people express hate toward others: Politicians. Journalists.

Christians. Muslims. Jews. Israelis. Zionists. Palestinians. Anyone more — or less — religious. African-Americans. Border wall advocates or opponents. Trump voters. Hillary supporters. Illegal immigrants. Radio and TV talk show hosts. Democrats. Republicans. Environmentalists. Socialists. Capitalists. Gun rights or gun control supporters.

“The trouble is that people who are filled with hatred are always sure they have a very good reason,” Adar explains. “In fact, they are sure that what they feel is not really hatred — it’s just a reasonable dislike.”

Who wants to be a hater?

And yet, “how easy and fun it is to hate people,” bemoans aish.com contributing author Keren Gottleib. “(W)hen it comes to finding the negative qualities in others, our imagination becomes a veritable fountain of ideas.”

According to contemporary psychologists, our dual cognitive processes are partly at fault, Brawer explains: “Intuition is subtle, emotive, and happens with rapid flashes of moral judgment that occur effortlessly… In fact, tiny flashes of disgust, disdain, or anger can lead us to dislike something even before we know what it is.”

Our more deliberative reasoning process then tries to justify those initial judgments.

“Convinced by our own arguments, what was a momentary emotive flash of dislike becomes entrenched hatred,” Brawer writes.

And as society becomes more partisan, it’s ever harder to move beyond our own worldview, she concludes, and sinat chinam runs rampant.

So what do we do? Lamentations starts the search for a solution to this baseless hatred by posing a question: “Eicha – How did this alienation come about?”

However, the word eicha’s first appearance is in Genesis, when God asks the disobedient humans in the Garden, “Ayeka (the same Hebrew root) — Where are you?”

Not physically where, but emotionally and spiritually, explains personal development coach Nina Amir. “Where are you in this story, and where do you want to be in the future?”

From eicha to ayeka, these linked words suggest that it’s not enough to ask “How did it happen,” as if you’re not part of the problem. These questions challenge us to contemplate our own role in both the problem and the solution, writes Rabbi Kenneth Brander.

Consider these perspectives as well:

Psychology notwithstanding, take control of your own mind’s reasoning process, as God warned Cain. Don’t justify immoral conclusions.

“We hate when we can no longer see the other person as having the spark of the Divine within them, as human as ourselves,” Adar cautions. Accept that everyone, even your opposition, has a Divine spark. Search for it and spotlight it.

Brawer offers, “Learning to pause after an initial judgment, reflect, and (re)consider our opinions in light of other perspectives is essential. Listening to others, reassessing our claims of certainty, and developing empathy are initial steps to healing sinat chinam.”

Dennis Prager regularly tells his radio audience he seeks clarity over agreement. Listen and ask for clarification. Restate your opponent’s point of view.

Also, “don’t judge or jump to conclusions,” communications trainer Andy Eklund advises, “and avoid (cherry-picking) parts of the conversation that support your pre-existing beliefs, values or perceptions.

Congressman and former Navy SEAL Dan Crenshaw advises, don’t be so ready to pounce. Focus on common goals: “I want a southern border wall. You want a technological solution. We both agree on the importance of border security. Let’s start there.” And look for those things that bring us together as a country.

The Chasidic masters promote transforming baseless hatred into something different through compassion and kindness, writes scholar Ariel Mayse. The key is the sacred spark at the core of all thoughts, emotions, and character traits. Our job is to discover the spark.

“Hate evil,” the Psalmist wrote, but nowhere in the Bible are we commanded to hate the evildoer. We’re not to despise the enslaving Egyptians, not even the murderous Amalek.

Before leaving Sinai, God underscored the message, “Do not hate your brother in your heart.” Even when it appears to be reasonable, we are not to hate people.

Literature to share

A Heart Just Like My Mother’s by Lela Nargi. Anna is sure she can never compare to her kind, fun-loving, and creative mother. As the two travel around town, their adventures touch on Jewish holidays, foods, family history, even homelessness. Accompanied by warm and inviting illustrations, this beautifully written story begs for discussion on a range of topics. A highly-recommended gem.

God is in the Crowd: Twenty-First-Century Judaism by Tal Keinan. Part autobiography, part philosophy, and part imagineering, God is in the Crowd explores the interrelationship of secularism, Judaism, Israel, America, and crowd theory in beautifully written prose. Keinan’s out-of-the-box thinking is fascinating and challenging, and his personal vignettes range from entertaining to gripping. Well worth reading.

To read the complete April 2019 Dayton Jewish Observer, click here.