A 60-year friendship, 112 years in the making

Dear friends recall their grandfathers, a Reform and an Orthodox rabbi in Dayton more than a century ago

By Marshall Weiss, The Dayton Jewish Observer

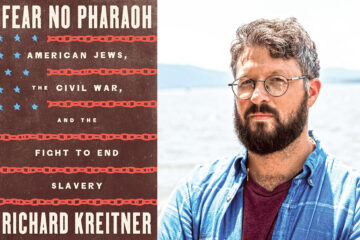

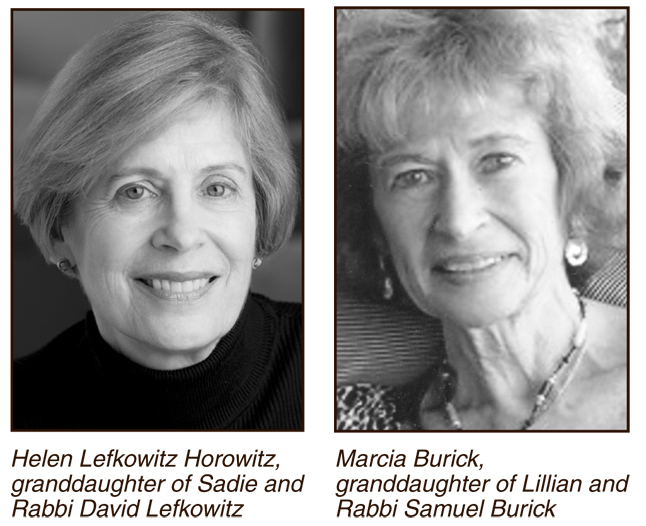

This summer marked the 60th anniversary of the opening of Goldman Union Camp Institute, an overnight summer camp of the Reform Jewish movement, in Zionsville, Ind. It also marked the 60th anniversary of a dear friendship that began there, between Marcia Burick and Helen Lefkowitz Horowitz. And as they discovered that summer of 1958, they were rekindling a family friendship that began in 1906, when their grandfathers — both rabbis in Dayton — first met.

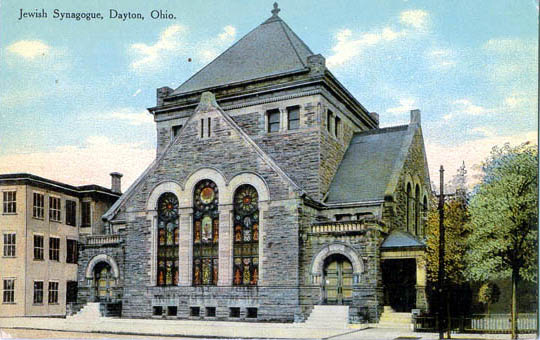

Helen’s grandfather was Rabbi David Lefkowitz, of Dayton’s Reform congregation, B’nai Yeshurun — now Temple Israel — from 1900 to 1920.

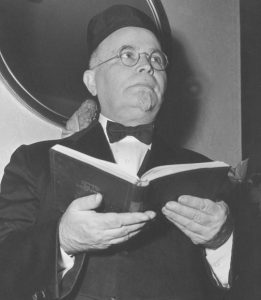

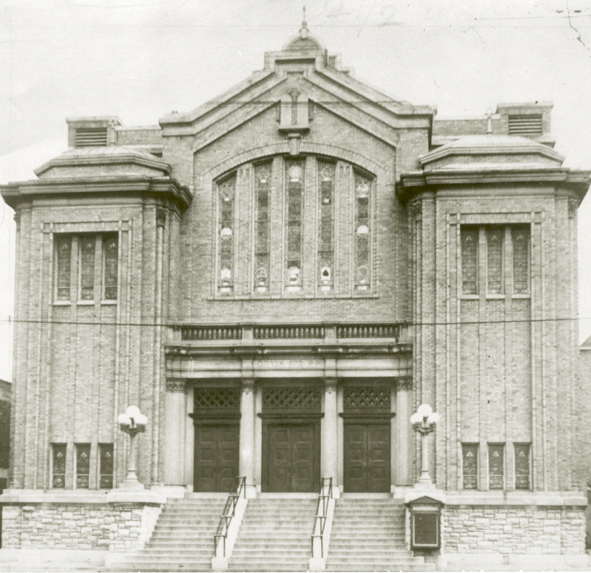

Marcia’s grandfather, Rabbi Samuel Burick, served the Lithuanian Orthodox synagogue, Beth Abraham, from 1906 to 1949. The rabbis, who came from distinctly different Jewish backgrounds, developed a close bond. Together, they worked for the betterment of the Jewish community and to bring it closer together.

Marcia, who lives in Northampton, Mass., and Helen, who lives much of the year in Cambridge, Mass., shared their recollections with The Observer.

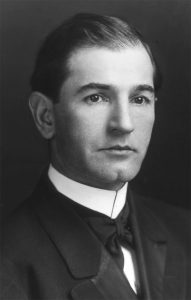

David Lefkowitz arrived here first, beginning his work at B’nai Yeshurun as a student rabbi.

“My grandfather, in the year 1900, was in his final year at Hebrew Union College in Cincinnati,” Helen says. He met his wife, Sadie Braham, when he boarded in her family’s home.

Helen said HUC’s founder, Rabbi Isaac Mayer Wise, gave her grandfather a wooden Havdalah spice box before Wise died in March 1900; the spice box was passed on to her.

Lefkowitz was born in Eperies, Hungary in 1875. His widowed mother brought him and his two brothers to the United States around 1881. Their mother was unable to support the family, and she abandoned Lefkowitz and one of his brothers at the Hebrew Orphan Asylum in New York. Lefkowitz lived there from 1883 to 89.

“It was a German-Jewish philanthropy to civilize Russian-Jewish children,” Helen says of the orphanage.

“While he went to City University, he did work at the Hebrew orphanage as a proctor to the children,” she adds. “And then, it was not an unusual thing that there was a connection to Hebrew Union College in Cincinnati.”

In Dayton, Lefkowitz quickly gained a reputation as a social reformer and sought-after speaker in the general community. Non-Jews began attending the young rabbi’s sermons at his temple, on Jefferson Street between First and Second Streets. He began receiving invitations to speak at civic events: to the student body of Steele High School in 1903, and on a lecture series at Christ Church also in 1903.

Lefkowitz would also attempt to bridge gaps among the distinct groups that comprised Dayton’s Jewish community.

“My grandfather,” Marcia says of Samuel Burick, “had come from Poland where he was trained, and then he went to Canada and then to Gary, Ind. There was another wife who died but nobody ever talks about. And then he came to Dayton, single, maybe six years after Rabbi Lefkowitz came.

“Rabbi Lefkowitz greeted and welcomed my grandfather into the community and invited him to the temple. And they became friends.”

But leaders with Burick’s Orthodox synagogue were not pleased with this.

“The powers that be at the synagogue, the Wayne Avenue Synagogue,” Marcia says, “wrote him (Burick) a letter, castigating him for going to be with a Reform rabbi. I’m not sure castigating is the right term.”

Helen picks up the story. “I think they censured him,” she says of Burick, who was about 25 years old then.

“My grandfather always laughed about it in later days,” Marcia continues. “He said that he got the hechsher (kosher certification) in reverse. He said, instead of the Orthodox rabbi giving the hechsher to the Reform rabbi, Rabbi Lefkowitz gave him the hechsher of approval.”

Members of Dayton’s Weisman family brought a cousin, Lillian Solnetzky, over from Russia in 1908 to become Burick’s bride.

“How could they stand to have a single rabbi?” Marcia says of her grandfather’s congregants.

Out of Zionsville

Marcia and Helen met through NFTY, the National Federation of Temple Youth.

“I was secretary of Ohio Valley Federation of Temple Youth,” Marcia says, “and I spent a lot of time my senior year going with Elmer and Dorothy Moyer. Dorothy and my mother (Rae Burick), did every philanthropic thing there was to do in Dayton together.”

The Reform movement had put Elmer Moyer in charge of selecting the site for a regional Reform overnight summer camp.

“I traveled with them on four or five different weekends, all over the area,” Marcia continues. “And they found a camp in Zionsville, Ind. Within two or three months, they bought the camp and got it ready for the summer of ‘58, which was the summer I had graduated from high school (Fairview) and was about to go off to college.”

The camp hired Marcia for that first summer as its secretary, “a fancy term for the person who stocked the canteen and carried the laundry into town, and fell in love with the president of NFTY,” she quips.

Helen, whose father was a rabbi in Shreveport, La., was president of the Southern Federation of Temple Youth. She arrived at the new camp as a high schooler.

“We got to chatting, because Marcia sat sort of in the front as you walked into the building,” Helen says. “She was older and gorgeous, of course. I learned that she was about to go to Wellesley College. Wellesley was on my radar list. So Marcia was there when I arrived as a first-year student, and she was living in a dormitory across the way.”

When Helen first arrived at Wellesley, she says, “the first thing Marcia did was to call me to say, ‘I’ve got tickets to the World Series and I’ve got one for you, Helen.’ I said, ‘I’m terribly sorry, Marcia. But I’m not interested in baseball.’”

Helen didn’t realize how important sports was to the Burick family. Marcia’s father, Si, was the longtime sports editor of the Dayton Daily News.

“Well, she managed to forgive me over time!” Helen says.

Marcia would go on to work in government at various times in her life.

“I taught a course on reinventing government and government reform in a number of places,” she says, including in Lithuania and in the Baltics, where she’s searched for her roots.

Helen received her master’s and Ph.D. in American civilization from Harvard and became a history professor with a specialty in American cultural history. She’s taught at MIT, Union College, Scripps College, USC, and on the faculty of Smith College from 1988 until her retirement in 2010. During her 22 years at Smith, Helen lived only a few miles from Marcia.

“Marcia and I used to always go out and have a glass of wine at the Hotel Northampton on her birthday,” Helen says.

One Passover Seder that Marcia hosted ended up a who’s who of descendants of Dayton rabbis, including Helen; a great-granddaughter of Rabbi Philip Weisman, who served Beth Jacob in the 1890s; and a granddaughter of Rabbi Selwyn Ruslander, Temple Israel’s rabbi from 1947 until his death in 1969.

The German/Eastern European Jewish divide

In the early 1900s, the established, acculturated German Jews — successful merchants and professionals who had arrived in Dayton beginning in the 1840s — comprised the Reform Jewish community. They lived downtown in the area of North Robert Boulevard.

Their poorer Eastern European cousins, who began arriving in the 1880s due to raging antisemitism in the Russian Empire, made their homes in the vicinity of Wayne Avenue between Fifth and Wyoming Streets in the East End, down to South Park.

Dayton’s Eastern European Jews prayed at Orthodox synagogues: Russian Jews at Beth Jacob, 358 E. Wyoming St., and Lithuanian Jews at Beth Abraham, 530 S. Wayne Ave.

Helen says the grandfathers refused to let the German/Eastern European Jewish divide stand in their way.

“They worked at it, even though it was initially criticized,” she says.

Crisis and need ultimately nudged segments of Dayton’s Jewish community closer together, albeit reluctantly.

In 1910, Lefkowitz brought together businessmen from his German-Jewish congregation to establish the Federation of Jewish Charities of Dayton to provide impoverished Jews — generally the Eastern Europeans — with interest-free loans, food, clothing, and coal.

Two years later, the Jewish Federation formally asked officers of Beth Abraham and Beth Jacob synagogues to send representatives to serve on the Federation board. Minutes from the time indicate that Beth Abraham did, but Beth Jacob did not respond; the congregation’s sense of dignity may have been the reason.

In 1927, Harold Silver, of the Bureau of Jewish Social Research, wrote that the Jewish immigrants of Eastern Europe “made no secret of the fact that in addition to desiring a kosher ritual and to help the poor in their own spirit, they wanted to show the German Jews that they were not schnorers (moochers) or parasites.”

Of the German Jews, Morris D. Waldman, founder and head of numerous national Jewish programs, wrote in 1916, “It has been customary for the early settler to regard the later arrival as inferior. The tendency on the part of earlier German Jewish settlers to look askance at the later Russian Jewish immigrants was not to be wondered at.”

The Great Flood of 1913, and then the First World War united Dayton’s Jewish community more than ever before.

“They worked together on flood relief,” Marcia says. “That was the big thing my grandfather talked about. After the flood, when Rabbi Lefkowitz helped rescue people, and then founded the Red Cross (in 1917), he involved my grandfather and grandmother in that.”

The Jewish Federation, under Lefkowitz’s guidance, provided relief loans for those hit hardest by the flood. By 1915, several borrowers could not repay them, and the Federation set aside loans “on which payment would be a hardship.”

When Beth Abraham dedicated a new Torah scroll in September 1913 to replace one that was destroyed in the flood, Lefkowitz joined Burick to help officiate at the ceremony.

Beth Abraham’s woodframe building was also washed away in the flood. And when Beth Abraham dedicated its new building at the same site in 1918, along with Burick and out-of-town rabbis who addressed the congregation in Yiddish, Lefkowitz delivered a speech in English.

With the increase in transients coming through Dayton, the two worked with the Federation to care for those who were Jewish.

“He never knew how many people would be at the dinner table,” Marcia said of her grandfather.

Beginning in 1916, all segments of Dayton’s Jewish community would meet together to raise funds for Jewish war relief in Europe, to increase the number of local Jews enlisting in the armed forces when the United States entered the war, and even to celebrate the Balfour Declaration, “in regard to the resettlement of Jerusalem for the Jews after the war.”

Lefkowitz would move his family to Dallas in 1920, where he would serve as rabbi of Temple Emanu-el until his retirement in 1948; he died in 1955.

“He is remembered in Dallas mainly for his public opposition to the rise of the KKK,” Helen says. “He was outspoken on that at a time when it was considered quite dangerous, particularly for a Jew.”

Lefkowitz would become president of the Central Conference of American Rabbis, and later in life, had a radio show in Dallas.

Burick continued to play a key role in aiding observant Jewish transients, in consultation with the Jewish Federation.

“My grandfather had a stroke, I think in 1948,” Marcia says, “and he died in 1957. He was in a wheelchair for all that time, but his mind was there. He could talk softly.”

The year after Rabbi Burick’s death, Marcia came home from her summer at the Zionsville camp. She told her grandmother, “Bubbe Burick,” she had met Helen Lefkowitz, the granddaughter of Rabbi Lefkowitz.

Marcia remembers her grandmother’s reaction: “Oh, he was such a mensch. He was such a good friend. Yes, he was so good to us, and so welcoming.”

Marshall Weiss, editor and publisher of The Dayton Jewish Observer, is the author of Jewish Community of Dayton (Arcadia Publishing).

To read the complete November 2018 Dayton Jewish Observer, click here.