The heart of a son toward his father

By David Esrati

There were times when I felt cheated for neither having a middle name nor a middle initial. Dad’s middle initial was G. for Gideon, which wasn’t pronounced Gidi-on, but the Hebrew way, Gee-don. It took me a long time to realize it was the same name.

His father, a scion of a wealthy family, had his Ph.D. and M.D. by age 21. Dashing, with a dueling scar on his face, he reportedly had a white horse in college where he was quite the big man on campus.

A son of the owners of a German mining locomotive company, my grandfather married a socialite with great legs and an eighth-grade education: my grandmother, the daughter of a Berlin lumber baron.

In 1933, my grandfather realized that Germany wasn’t going to be a good place to be Jewish. So he scouted out a way to get out of the country and found a restaurant on the Swiss border where the window of the men’s room was in Germany. He made this trip multiple times, smuggling out my 6-year-old father, Stephen; my grandmother; and later, in 1939, her sister and her daughter. Some of the family jewelry was smuggled out inside a small pillow.

My father’s wealthy grandparents wrongly assumed that the Nazis wouldn’t have any reason to bother with them. His paternal grandmother, the last of them, died in Theresienstadt on March 4, 1943. She was deported from Berlin on Aug. 17, 1942 in the first transport of elderly Jews. The German’s meticulously documented her death as “enteritis,” which my father noted in his genealogy software as a fancy way of saying she starved to death.

The survivors in my family made their way to Palestine where my grandfather practiced medicine and terrorism. Trying to expel the British put him in esteemed company. According to my father, Golda Meir was one of the people who frequented my grandfather’s clinic; weapons frequented his clinic too.

It was there that my family switched its name from Hirsch to Esrati, the name of a laundress. Dad liked the name, and since it happened to be Sephardic — which matched my grandfather’s lineage — they adopted it to ditch the unpopular German roots. A translation gaffe happened when my grandfather arrived at Ellis Island in 1939. Dr. Esrati spoke no English, so his German way of phonetically spelling the Hebrew made our family, as far as I know, the only Esratis on the planet.

There are Ezrattys and Isradis and other variations, but I’ve never met another Esrati. In the travels of my youth, I’d scour the white pages phone books in hotels, and now Google seems to have confirmed our name’s uniqueness.

Dad enlisted in the U.S. Army and was sent to the Italian-Yugoslavian border after the war had ended in Europe but was still going in the Pacific. He was an MP, trying to cut off Nazi escape routes. But he was also stealing weapons and helping smuggle them to Palestine.

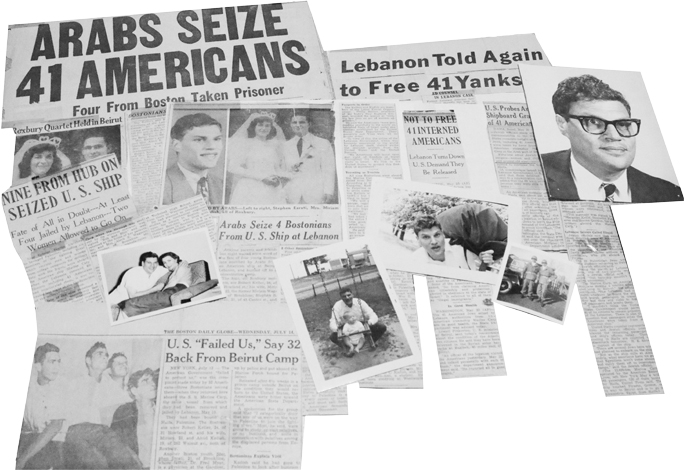

In 1948, he and a bunch of Betarim (members of a pre-state Zionist paramilitary unit) had loaded onto a former troopship, the Marine Carp, to fight in the Israeli War of Independence, in violation of the U.S. Neutrality Act. The ship was stopped in Lebanon. It was demanded that the men of military age leave the ship. This was the day after Israel declared its independence. Sixty-nine, including 41 Americans, were escorted off the ship at gunpoint.

My father volunteered to go first.

On my recent, first trip to Israel, I sat in the kitchen with former Israeli Defense Minister Moshe “Misha” Arens and his wife, Muriel. She was on that ship, and Misha had organized the trip. She told me that she was absolutely sure they were going to be shot on the dock. When they instead loaded them onto trucks, she thought they were being taken somewhere else to be shot, and that the 69 would never be seen again.

That’s when my father became one of the first hostages in the modern Middle East, long before the Iranian Embassy siege. They were released after two months in captivity. Dad lost almost 30 pounds. Never one to follow the crowd, he jumped ship in the Azores on the trip home, which ended up being a slight delay. When he eventually returned to the states later in ‘48, his passport was confiscated for six years. Dad was deemed a security risk and kicked out of ROTC; he was also held in “pipeline” instead of being sent to Korea.

When the Freedom of Information act was passed in 1971, he requested his files. They were at least two inches thick, with lots of black redactions.

As soon as he got his passport back in 1954, he returned to Israel. While living on a kibbutz, he became engaged to a woman named Lily, whose father was excited about having an American son to help his export business expand in the States.

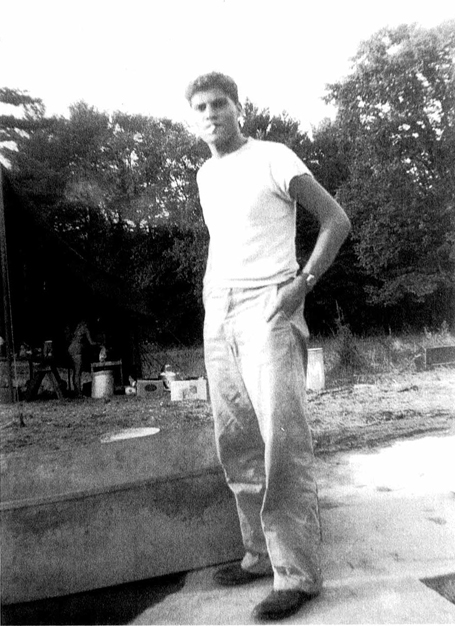

My future mother, Nina, showed up at the kibbutz looking for a husband and saw him as she stepped off the bus in Hasolelim. He was marching across the field in khakis and a white sleeveless T-shirt, a cigarette hanging from his mouth and some kid “little Joey” tagging along. She made her way over to talk to him at the dining hall. They began a conversation that lasted days. He went to get the ring back from Lily after day four or so. Nina and Stephen moved in together.

Nina became his wife, several times. They married on the kibbutz, on the ship to England, and then for the family in England. When he died, they were short just three days of 62 years.

My arrival on planet Earth changed my father’s life trajectory. He was a journalist with The Cleveland Plain Dealer for most of my childhood. He instilled in me a reporter’s curiosity. Dad would never drive the same way twice, instead looking to learn a city.

Some of that came from him driving a cab to put himself through college at Boston University, where he earned both undergraduate and master’s degrees in political science. It was also where he used to lunch on Thursdays with a doctoral student and debate with him about peaceful protest versus armed rebellion. That student was named Martin, later known as Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.

My Dad, Steve Esrati, passed away on Aug. 18 at the age of 89 at the Dayton VA Hospice. He left his body to Wright State University Boonshoft School of Medicine.

Dad wrote three books: The Tenth Prayer, a story of Israel; Comrades Avenge Us, historical fiction; and Dear Son, do you really want to be an American? He wrote the last one for me on my 18th birthday. We were living in Canada from 1968 to ‘70, and the book’s intent was to help me make up my mind on citizenship since back then, dual citizenship wasn’t allowed. It was an unfiltered version of American history as seen from an immigrant to his first generation son. That book, although only about 80 pages, helped me understand that we get the government we fight for, not what is given to us.

David Esrati owns The Next Wave ad agency and is active in local Dayton politics. He follows in his father’s footsteps, doing citizen-driven journalism on his blog, esrati.com. He is still searching for his own Mrs. Esrati.

To read the complete October 2016 Dayton Jewish Observer, click here.