Human nature

Jewish Family Education

Jew in the Christian world by Candace R. Kwiatek, The Dayton Jewish Observer

“This is an island. At least I think it’s an island…Perhaps there aren’t any grownups anywhere.”

“Nobody knows where we are,” said Piggy.

…Ralph pushed back the tangle of fair hair that hung on his forehead. “So we may be here a long time.”

Thus begins William Golding’s novel Lord of the Flies. Unrestrained by rules, adults, or society, two dozen boys marooned on an uninhabited island struggle between civilization and savagery. Barbarity threatens to triumph. Golding’s fictional exploration of human nature sparks questions about the fundamental issue of what it means to be human.

In both Jewish and Christian Scriptures, Christianity finds confirmation that humans are created in the image of God.

Echoing “And God created man in His own image (Genesis 1:27),” the Christian New Testament teaches, “A man … is the image and glory of God (1 Corinthians 11:7).”

According to most Christian views, humans have a spiritual nature that includes free will, the capability of moral awareness and rational thought, and the ability to reflect God’s attributes such as compassion, truthfulness, and patience.

Divinely created and pronounced “very good” (Genesis 1:31), human nature was perfect in the beginning. But Adam and Eve disobeyed God by eating the fruit of a forbidden tree in the Garden of Eden, bringing death and sin as a permanent corrupting influence into the world.

Most Christian traditions teach that the human soul was permanently damaged, resulting in a predisposition to sinful behavior — humankind’s “fallen nature.”

Many Christians also subscribe to the doctrine of “original sin,” the idea that all humans after Adam and Eve are born with the stain of sin. Although humans must struggle against their evil nature to obey God and do good, in Christianity, the individual can only avoid eternal damnation through acceptance of Jesus as Christ (messiah) and savior, whose sacrificial death liberates the believer from sin and guilt.

In Jewish tradition as well, the early biblical narrative describes the nature of humans. God finishes creating all the living creatures and says, “Let us make man in our image, after our likeness (Gen. 1:26).”

Commentator Dennis Prager concludes that humans are like both animals and God, with qualities that are both material (physicality and life) and spiritual (consciousness and holiness).

The Bible emphasizes humans’ Divine nature by repeating, “And God created man in His own image, in the image of God He created him (Gen. 1:27).”

Medieval Jewish commentators Rashi and Rambam elaborate, explaining that humans have the ability to understand, analyze, reason, and predict by using the intellect rather than physical senses.

Jewish ethics and prayers further interpret “in the image of God” to mean the ability to imitate God’s qualities such as justice, mercy, and lovingkindness, and the free will to choose to do so.

While God laments humankind’s appetite for wrongdoing —“The tendency of man’s heart is toward evil from his youth (Gen. 8:21)” — Judaism does not hold the view that humans have a sinful nature that’s permanently fallen or stained by original sin.

At the same time, the “very good” nature instilled at Creation does not mean that humans are born good, as Enlightenment thinkers proposed.

Judaism teaches that human beings are born neutral, with both a good or altruistic impulse (yetzer tov) and an evil or selfish impulse (yetzer ra). The yetzer tov’s moral conscience is the balance to the yetzer ra’s amoral desire to satisfy personal needs, regardless of the consequences.

The rabbis of the Talmud question why God exclaimed that creation was very good when it included the yetzer ra (Genesis Rabbah 9:7). Rabbi Nahman replied that, “were it not for the evil inclination, men would not build homes, take wives, have children, or engage in business.”

Contemporary scholar and author Rabbi Joseph Telushkin explains that the selfish motives of the yetzer ra such as pride, lust, immortality, and wealth can create great things. “From Judaism’s perspective…greatness of character is not measured by our not having an evil inclination, but by our success in controlling it.”

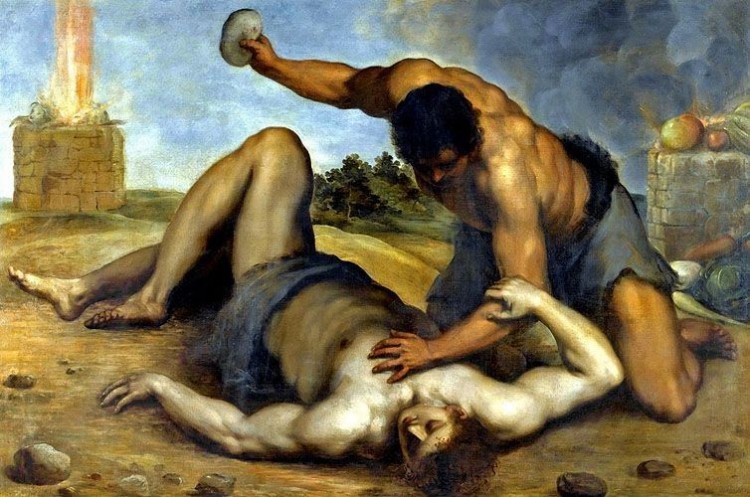

As for Adam and Eve in the Garden, their story is not central to the Jewish understanding of human nature. Rather, it is the story of Cain, where the word sin first appears in the Bible.

“Why are you distressed, and why is your face fallen?” God asks the jealous Cain. “Surely, if you do right, there is uplift. But if you do not do right, sin crouches at the door; its urge is toward you, yet you can rule over it (Gen. 4:6-7).” It highlights the Jewish view that human nature is not sinful; only human behavior can be.

To read the complete July 2015 Dayton Jewish Observer, click here.