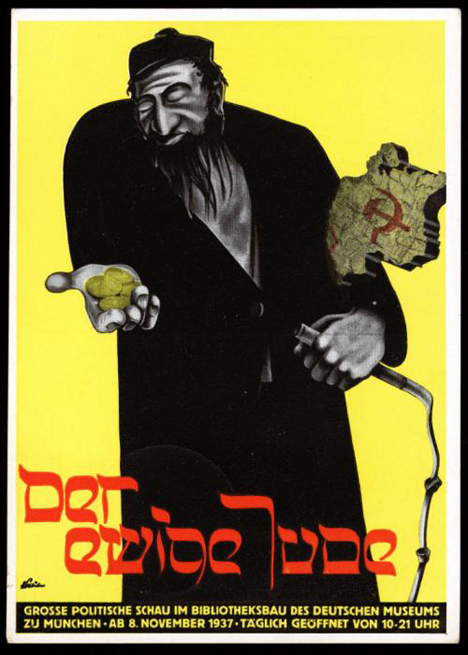

The eternal Jew

Jew in the Christian world

By Candace R. Kwiatek, The Dayton Jewish Observer

During a recent conversation, a Jewish friend criticized a Forward article highlighting the wealthiest Jews in America, concerned that it would validate stereotypes of Jews as greedy, wealthy controllers of the economy.

Her concern is not unfounded, as recent Anti-Defamation League studies about Jews and money have shown.

According to the ADL, while only 10 percent of Americans are appraised as being definitively antisemitic, worldwide that number jumps to 26 percent, or 1.1 billion adults.

Jew-hatred has been a permanent feature of Jewish history.

Although its statistics have varied across the centuries and continents, “no hatred has been as universal, as deep, or as permanent as antisemitism,” conclude authors Dennis Prager and Joseph Telushkin in their 1983 book, Why the Jews? The Reason for Antisemitism.

Why? Historians offer a partial answer.

Pagan bewilderment

The biblical Israelites’ belief in a single invisible God and their unwillingness to acquiesce to the gods and traditions of the dominant pagan culture aroused curiosity and bewilderment.

This refusal to conform periodically generated suspicion and accusations of disloyalty, civil and political tensions, and strategies for forced assimilation, exile or genocide.

By the cusp of the Common Era, Judaism had become both a cultural threat to universal Hellenism and a political threat to Rome’s military image.

To undermine the Jews, classic rhetoric began to vilify them not only as being disloyal and troublemakers, but more specifically as “a diseased race of lepers and a godless people,” barbaric, superstitious, and lazy; guilty of “kidnapping Greeks to fatten and sacrifice,” and “conspiring to take over the empire.”

Religious demonization

Using biblical text and tradition, early devotees of Jesus tried to persuade fellow Jews to join their new sect.

Pointing to the destroyed Temple and Jewish dispersion as evidence that God had rejected the “Chosen People” and the Law (Torah), early Christians championed the believers in Jesus as God’s “new Israel,” keepers of the “new covenant” of faith.

However, Jews largely rejected this. Bitter about this roadblock to Jesus’ return, Christianity condemned the Jewish response as a rejection of God, a sign of “possession by the devil.”

As Jewish intransigence continued, it threatened the notion that Christianity replaced Judaism and the Jews. A campaign of delegitimization followed: Judaism was equated with devil worship; synagogues were castigated as dens of thieves; Jews were described as miserable and degenerate, perpetrators of deicide, and justifiable targets of violence.

Jews were to be humiliated and defeated, living examples of the consequences of rejecting God’s truth.

By demonizing and dehumanizing the Jews, church leaders effectively relegated them to permanent outsider status.

As Christianity swept through Europe, justification for Jew-hatred shifted. Largely ignorant, fearful, superstitious, and xenophobic, medieval Christians blamed the despised Jews for every disaster.

Skilled in commerce and urban trades, Jews were accused of unfair competition and stealing jobs. Accomplished in finance, Jews were resented for their affluence, accused of owning the banks and controlling the economy, and blamed for all financial woes.

Ritually and culturally foreign, Jews were the targets of perfidious allegations: the blood libel, ritual murder, and poisoning wells.

As in earlier pagan societies, Christian Europe devised strategies to excise the Jews through marginalization, forced conversion, exile and annihilation.

Secular pseudoscience

When the Enlightenment arrived in Europe, it replaced religion and tradition with reason and scientific knowledge.

Increasingly secular, the values of liberty and equality it championed encouraged freedom from religious conventions and equality through assimilation.

Exclusion could only be justified by “scientific” evidence. Race, defined as “observable physical traits and moral qualities,” became the yardstick by which Jews were measured. Jews were backward, clannish, usurious, and maleficent.

Judaism nurtured illiteracy and superstition, ridiculous customs, and “historically proven” traits of dual loyalties, anti-Christian bias, and ritual murder.

While Montesquieu and other leaders called for the Jews to renounce Judaism and become enlightened, the German philosopher Johann Gottlieb Fichte theorized that Jews were unchangeable and incapable of conversion, resolvable only by “cutting off all their heads,” foreshadowing things to come.

Meanwhile, with the Enlightenment came emancipation, and Jews took advantage of new opportunities in occupations, education, and cultural life.

Highly successful, they were accused of controlling the banks, media and film industries, and politics; denounced as communists, capitalists, and exploiters of labor; and condemned for causing wars, inciting nationalism, and aspiring to world domination.

After three millennia of such degradation, marginalization, and dehumanization of the Jews, the Holocaust was a foregone conclusion.

Historians have suggested that political, cultural, religious, and economic factors have variously caused antisemitism, but in reality these have only been its transitory battlefronts.

The source of Jew-hatred has always been Judaism itself, Prager and Telushkin conclude, an inspired tradition that testifies to a single God who demands ethical behavior.

This tradition of beliefs, values, laws and customs has been upheld by its defiantly enduring and thriving people, challenging all other ideologies in every age and place.

Literature to share

Playing with Fire by Tess Gerritsen. From a bestselling author of romance, medical, and crime novels comes this historical thriller. Beginning in Rome with a violinist’s discovery of an unusual musical score in an old bookstore, two stories of the music’s diabolical effect on the musician’s young daughter, and the discovery of its origins in 1930s Venice collide.

The Girl in the Torch by Robert Sharenow. Drawing from his own family’s background, this award-winning author of young adult literature offers a thoughtful picture of the immigrant experience at the turn of the 20th century. Set at Ellis Island and the Lower East Side, this adventure tale highlights universal themes of grit and adaptability that transcend the diversity of ethnicities and situations.

To read the complete February 2016 Dayton Jewish Observer, click here.